Live a life of kindness. – Lilly Constance

The names in this post will be changed to protect students’ privacy.

At the end of each week we take turns presenting that week’s progress to the faculty at UNIVEN. Each presentation is carried out by one U.Va. student and one UNIVEN student and a couple weeks back it was my and Lufuno’s turn. Lufuno didn’t have much experience using PowerPoint so we spent an afternoon familiarizing him with the program. Then we put together a presentation on the work that our child development group had done that week.

The morning of the presentation Lufuno and I met up before everyone else to practice our spiel and go through how we were going to switch off between slides. As we sat on a bench outside our meeting space the following scene unfolded:

Lufuno–earnest, humble, and one of the top nursing students in his class–was sitting rigidly on the bench, facing straight ahead intently focused on memorizing the bullet points on each of the slides. Alternatively, I–enthusiastic and comparatively unconcerned about the task at hand–was trying to make Lufuno relax. I sat facing towards him and every time Lufuno asked a question I would try and make eye contact with him or smile encouragingly to let him know that we were on the right track. But to my growing frustration, every time I tried to make eye contact with Lufuno he would avert his eyes or look the other way. It finally became too much and I just burst out laughing.

“Lufuno, you know, in the States when we’re trying to show someone that we respect or support them, we look them in the eye.”

Lufuno whipped around and this time he did look at me, mouth open, eyes wide.

“Wow!” He just laughed and laughed. “Here, when I want to show some one respect or support I would never look them in the eye.” The both of us shook our heads and let out sigh of relief as it became apparent that each thought the other had been behaving strangely.

“Alright, out with it Lufuno, what are other things that I do that seem strange or awkward to you?”

He gave me a pained smile.

“Ahhhh well, you see…” He broke into laughter again.

What followed was a long conversation between the two of us about cultural differences in interpersonal interactions. In particular with greetings and farewells, it seemed that there were a lot of subtleties I had missed out on the first time people had been trying to teach me how to greet people of different statuses or genders. In particular, it seemed that when I said my general “Aa” (“hello” for females) to people I had been bowing in the the wrong direction. Instead of bowing slightly to the right–the signature of the female greeting–I have been bowing slightly to the left–the signature of the male greeting. Talk about botching first impressions. Though most of the people that we met were very forgiving of our communication slip-ups since we were foreigners, it suddenly dawned on odd me how my attempts at greeting people must have seemed: “Hello, my name is Claire, and in case you were curious, I swing both ways.” Maybe I exaggerate, but the unrestrained peal of laughter that Lufuno let out when I demonstrated to him how I had been greeting people for those first couple of weeks seemed to imply just that. Yet despite all this, Lufuno was incredibly patient with me, and from that point on in the summer he always went out of his way to offer me small lessons in Venda culture.

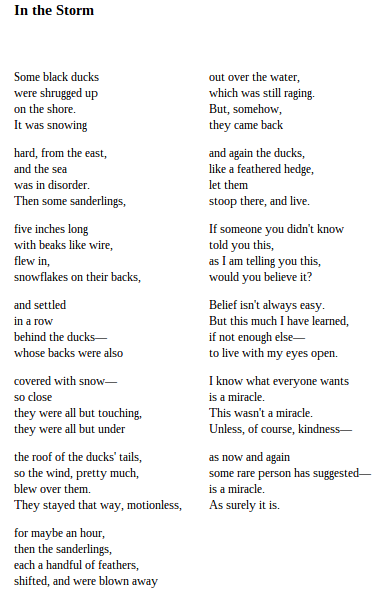

This week I read Thirst, a collection of poems by Mary Oliver that she wrote after the death of her partner of over thirty years that chronicles for the first time her discovery of faith. I have always been a fan of Mary Oliver but wanted to read this collection while I was in Limpopo because I felt her literary travels through the landscape of sorrow might offer an interesting parallel to life in a foreign country. One of the poems in Thirst that struck me the most was called “In the Storm.”

Though one might think that when traveling in a foreign country you would be most startled by the exotic, I found that I have been most moved by the commonplace: the meals people cook for us, conversations we’ve had or any of the many times people spontaneously break into song.

I suppose what I’m really saying is that I continue to be surprised by kindness. I think that more often than we like to admit, we look at kindness as a kind of currency: something that you give to people in exchange for something else. Because of this, we are always somewhat taken aback by kindness that we don’t “deserve.” We’re almost suspicious of it or assume that there must be some kind of ulterior motive. My entire stay here in Thohoyandou has been a continual lesson in the miracle of kindness.

Kindness, to me, seems to be the language of solidarity. The Catholic Church teaches that loving thy neighbor has global dimensions in a shrinking world. Though on one level this means that we are our brothers and sisters’ keepers wherever they may be, I think that this is also just another way of saying that we cannot put limits on when and where kindness is due. Yes, we can prioritize foreign aid; yes, we will always have the opportunity to be systematic about how we invest in developing countries, but we don’t have room to compromise kindness.

I’ll leave you with my favorite lines from God Bless You, Mr. Rose Water by Kurt Vonnegut. It comes as part of a baptismal speech Mr. Rosewater is preparing for his neighbor’s twins:

Hello, babies. Welcome to Earth. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. At the outside, babies, you’ve got about a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies—God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.

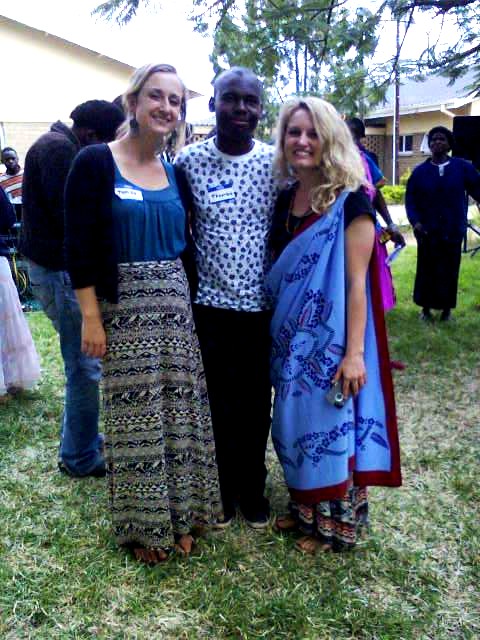

Visiting Tiyani Clinic with our UNIVEN Partners.

Claire Constance is blogging from Limpopo, South Africa, this summer for the Summer Internship on Lived Theology. Learn more about Claire and the internship program here, and read more internship blog posts here.