Last fall at U.Va., I took Dr. Paul Jones’ class on “Elements of Christian Thought.” It is considered one of those “must-take” classes by many of my friends, and I was really looking forward to reading some of the church fathers. Aside from referring to him as “John Paul Jones” in my first discussion section, I thought the class was going pretty well. Until we got to the debates about the theological significance of the nature of Christ, that is. Was Jesus 100% human and 100% divine? Was he either all divine or all human? Was he 99% human and 1% divine with a dash of salt? This was one of those moments where I started to get annoyed with Christian theology. How much does a later theological label on the saving work of Christ really even matter? It bothered me that ideologies that didn’t really seem THAT out there were labeled as “heresies” by the Church. Specifically, the Church’s stubborn insistence on the humanity of Christ threw me for a loop. I’d been in Christian circles my whole life, so I was prepared to give some sort of an answer (mostly centered on the logic of the atonement) should anyone else express a similar concern to me, but there was still something about it that didn’t sit well with me.

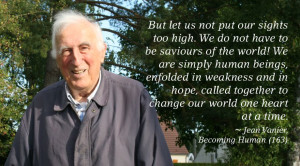

Okay, now flash forward almost a year. This week I’ve been reading a wonderful book by Jean Vanier called Becoming Human. Jean Vanier is a Catholic philosopher, theologian, and humanitarian passionate about including individuals with disabilities. In 1964, he left a prestigious teaching job to found L’Arche, a now international group of communities in which people with disabilities live together with able-bodied assistants. These groups center on the importance of community between diverse individuals and seek to embody the characteristics extoled by Jesus’ beatitudes (Matthew 5).

The way Vanier speaks of those with whom he lives — constantly referring to them as friends or teachers, only using the language of disability when it is unavoidable– reveals his deep commitment to the presence of the Imago Dei in all humanity. In his book, he speaks on the beauty of what he calls the “simple relationships” he has enjoyed with his friends at L’Arche. Far from making a condescending statement, Vanier is making a profound distinction between what can sometimes be the overly serious world of the mind and the celebratory world of the heart. As he states, “It has brought me back to my body, because people with disabilities do not delight in intellectual or abstract conversation.” Embodiment is key for Vanier.

This is something to which I can relate, having spent a few weeks at the Virginia Institute of Autism (VIA). Because most of the children in my classroom experience trouble communicating (almost all use iPads to speak rather than their voices), at first glance one might think developing a real relationship with them would be difficult at best. I know this was my thought a few weeks ago. And indeed, this is a common misconception about people with autism. Despite often significant difficulties with social interaction, they do not seem to need it any less. Sometimes, these methods of communication are simply more limited, and it takes the right supports to be able to engage these children in a way that allows them to express themselves. Take one student in our class for example: Corey. His favorite thing to do is play with pens. Talk about the simple things in life! He doesn’t even write with them, he just holds them and stares at them skeptically. Pens are the key to his heart. Or take for example Maria, one of the few students who does use spoken words to communicate. You will probably be met with a blank stare if you ask her what her favorite TV show is, but repeat the line “Clifford, come!” to her a few times and a huge grin spreads across her face. I think this is the kind of “simple relationship” that Vanier discusses. Everyone enters into the “world of the heart” in a different way, and sometimes it is through these simple connections that bring two people together more than anything else. When you are nowhere else but completely present with someone, is that not the best gift to give them? I think being and feeling “known” and understood is one of the most fundamental needs of a person. What a joy it is to find such pleasure in embodiment itself!

Vanier’s main project through the elevation of embodiment was to “become more fully human.” But as I begin to think about this in a more abstract way: what is so great about being human? It seems like if you ask most people, the whole “being human” thing is at best a mixed bag. What makes it an intrinsically good thing to embrace trauma, heartache and disease alongside friendship, love, and health? Humans appear to be the only creatures that feel this unique need, even conceiving as “noble” this thought of “embracing one’s full humanity.” Let me know if you see any frogs vigorously theorizing about how to make the most of their frog-ness.

Upon first glance, I judged this to be an unnecessarily pietistic and potentially prideful attitude towards human life. What’s the use in trying to make the entirety of “humanity” out to be worth pursuing on its own end when it is not clear that “humanity” really is all that and a bag of chips?

Now, I don’t know how much chips impact the quality of one’s humanity (although I can vouch for pretzels), but I began to see Vanier’s point when I considered its rich grounding in Christian theology. And it brought me back to my annoyance at that lecture almost a year ago. Just as I was brushing off the nobility of this pursuit of being human, I realized that on this very pursuit lay the whole of Christianity. In my last post, I mentioned the idea that God may be better explained by his actions in the world rather than his abstract attributes. According to the Christian story, the incarnation– the story of God himself becoming human– is not only the way in which God chooses to reveal himself to the world, but the mechanism through which he saves. For me, this also brought new meaning to those centuries-old debates about the divinity and humanity of Christ. It is precisely because Christ saw fit to enter into humanity that this is such a worthy pursuit for us. The significance of this doctrine is not merely abstract; it is profoundly personal. This absolutely central claim of a deeply relational God is what gives Christianity its uniqueness. The only way to follow Christ is to embrace humanity in the way he did. In a sense, becoming human is the most divine thing you can do.

*Names of the students at VIA have been changed to protect their privacy.

Vanier, Jean. Becoming Human. New York: Paulist Press, 1998. Print.