by Emily Miller, 2022 Undergraduate Summer Research Fellow in Lived Theology

Volunteering at the Albemarle Historical Society just the other day, I had a casual conversation with the librarian about the ways that Charlottesville was “ruled” by particular prominent families in the nineteenth century- certain last names come up over and over in her and my own research of local history. “Everyone was kind of related to everyone,” she told me- and for the history of First Baptist Church, I don’t think this sentence rings more true than for the Cabell family.

The history of Cabell influence in Virginia traces back to William Cabell, who came to the Jamestown settlement in 1726 from England. After spending time exploring the land that would later become Nelson county, Cabell received an initial grant of 6320 acres from King George I. Eventually, his land ownership would grow to exceed 40,000 acres of land in Central Virginia, thus beginning the Cabell legacy.

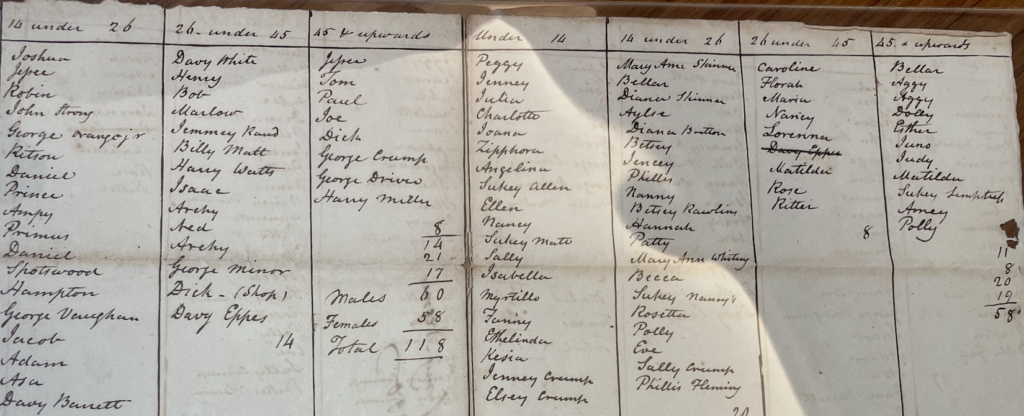

Cabell Hall of UVA is named for Joseph Carrington Cabell, who was recruited by Jefferson in the initial planning for UVA’s development. Joseph Cabell was strongly committed to upholding the institution of slavery in Virginia and, like his nephew, white supremacy. Records located at various UVA libraries discuss the Cabells’ dealings with enslaved peoples, one of which being the 1820 census of slaves- taken when Joseph Cabell was thirty two- pictured in part below.

According to Alan Taylor, UVA Professor, Joseph Cabell was particularly unforgiving in his management of slaves, “treat[ing] slaves as investments… he shifted and sold them to increase his profits, slighting their family relations as of little concern. When the estate manager, George Gresham, balked at the proposed changes as disruptive, Cabell wanted to fire him.” According to Taylor, Cabell would frequently have his slaves whipped or beaten, and slaves would frequently run away from the Corotoman Estate, where Cabell owned a share.

Joseph Cabell’s nephew, James Lawrence Cabell, was a professor of science at UVA, and eventually became the first president of the National Board of Health. In the meantime, Cabell wrote The Testimony of Modern Science to the Unity of Mankind, which highlighted his affirming beliefs about both eugenics and, namely, white supremacy. James Cabell also “solved” the University’s problems with obtaining anatomical subjects for study by encouraging the grave robbery of deceased, formerly enslaved African Americans at the University.

The power the Cabells had- over land, enslaved people, and understandings of race and science in Virginia- becomes more tangible when exploring their direct impact on First Baptist Church. According to the essay The Education of William Gibbons by Scott Nesbit, the first black pastor at First Baptist Church on Main Street, William Gibbons, was likely enslaved by none other than Arthur Gibbons, who is the brother in law of James Lawrence Cabell. Gibbons began preaching informally at Charlottesville Baptist while he was still enslaved in 1844 (likely as an aid to a white preacher, according to Nesbit), and became the official pastor at First Baptist Church on Main Street in 1868. William Gibbons would go on to marry Isabella Gibbons, a teacher at the Jefferson School, and Gibbons Residence Hall at UVA is named for the couple.

William served as an aid of sorts to Arthur Gibbons, and through social connections of Arthur’s was able to obtain an informal education that would have far exceeded most other African Americans of the day, earning him great respect in the church. However, Nesbit writes that at that time “often students would “teach” African Americans about racial hierarchy through acts of violence that interrupted black community life and reinforced blacks’ vulnerability and consequent dependency upon whites.” Orra Langhorne, a 19th Century writer for the Southern Workman magazine, wrote regarding William Gibbons that “it was rather amusing to the white boys… to see a Negro so anxious to learn.” It’s well worth noting that James Lawrence Cabell was teaching eugenic beliefs at UVA at the same time that William was enslaved there.

During the same year that William Gibbons became the preacher of First Baptist on Main, the congregation members were working on securing a church building. According to Richard I. McKinney in his book Keeping the Faith, there was a great deal of difficulty securing the deed for the church from a certain P. Cabell (I have had trouble finding this man’s first name, but McKinney is clear that he is of the Cabell family). The matter took five years to settle, as the buyers had to negotiate continuously with Cabell about specifically how much was owed to him and his assignees.

Anyone who attends UVA now can recognize the Cabell name. But before first hearing about James Lawrence Cabell in a theological bioethics class I took this past year, and before learning the history of First Baptist Church, I only knew the name as an academic building with a library that I liked. To find that the Cabells were a picture of domination in Charlottesville- over those enslaved and over the city itself- makes me think deeply about the land I walk on everyday here, for a long time owned in part by a family that went to great lengths to preserve white supremacy.

Learn more about the Emily’s Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship in Lived Theology here.

The Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia is a research initiative, whose mission is to study the social consequences of theological ideas for the sake of a more just and compassionate world.