May 9, 2024

Charles Marsh reflects on his 1994 Interview with Sam Bowers. His 1997 Oxford American article “Rendezvous with the Wizard”, is now available for the first time in digital format.

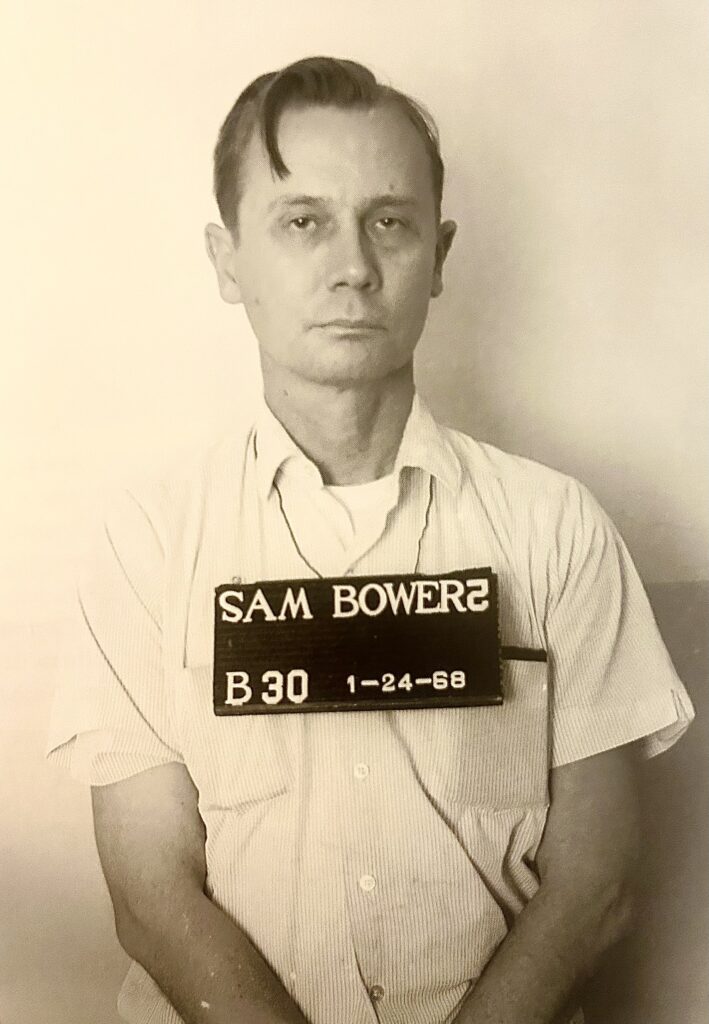

“WHEN THE INTERVIEW began it was hard for me to reconcile the man before me—calm and almost elegant in his pinstriped suit—with everything else I knew of him: that he had reigned over a campaign of terror in 1960s Mississippi. On that night, in the summer of 1994, the former Imperial Wizard of the Mississippi Ku Klux Klan had not yet been convicted of murder—not for his part in the 1964 deaths of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, nor in the 1966 firebombing death of Vernon Dahmer. He had served seven years in a federal prison for conspiracy to deprive Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner of their civil rights; and since being released, Samuel Holloway Bowers Jr. had been back in his hometown of Laurel, his life not so different from that of an aging Nazi in a Bavarian village. He read newspapers and magazines in the public library, went to church and taught Sunday school, and regaled old associates and new admirers with stories of his glory days. He also put his mind to working out a theology of ethnoracial nationalism.

“Bowers and I sat across from each other at a table at Uncle Roy’s Home Cookin’ and Barbecue, a cement block annex to the 16th Street Exxon. While I hadn’t expected him to show up in a white robe, the matching Mickey Mouse watch, belt buckle, and cuff links—and the missing front tooth—seemed to belie the pinstripes. What he said to me on the three evenings we passed together seemed, at the time, vicious but also almost quaint—which is to say, affected, prim, cunningly designed.

“But there were moments in the exchange when I got a glimpse of the tempestuous rage that had made Bowers the most feared White southern terrorist of the civil rights era. I recently reread my handwritten notes of those interviews and came across this passage: He starts talking about how much he hates liberals, or as he calls them “anarchists, communists, and demagogues of the Democratic Party.” He uses the word “academy” as a general description of the malign forces that threaten his ethnonational Christian mission. “I look on the academy with an obduracy and utter contempt. I hate it with a total hatred,” he says, as his tremulous voice breaks suddenly into raucous laughter: The pagan academic savants and the media whore—the whores of Baal!—will inevitably descend into a ‘behavioral sink’ and rot away.” But if it doesn’t, he adds, “there are men willing to sacrifice their physical lives in attacking the academy at the very center of its power and prestige.” Witnessing his narrowed eyes and increased physical agitation in this moment is to understand his gifts of manipulation and control—the ease with which he would have inspired White men to do his violent biding. Abruptly, his voice assumes a measure and refinement; he leans back in his chair resting his head in the cup of his hands; and begins to discuss his grand theory of history and his important place in its unfolding.”

This passage comes from the preface to the new edition of Marsh’s book God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights, appearing in August 6 as a Princeton Classic.

Throughout the coming months – as the nation celebrates the 60th Anniversary of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project – we’ll be posting field notes, interviews, historical documents, and outtakes from research in the years 1991 – 1996, the building blocks of the narrative.

Today we are delighted to share with you Charles Marsh’s essay, “Rendezvous with the Wizard”, published in the Oxford American, available for the first time here in digital format.

Yes, it’s fairly harrowing to realize that the “worldview” of the Imperial Wizard of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan of Mississippi and self-proclaimed Christian terrorist is no longer an idiosyncratic position forged in the crucible of the anti–civil rights movement by segregationists clinging to authority they’d quickly lose. Rather, Sam Bowers’ theories sound like talking points for a generation of Christian nationalists who hold political office, run think tanks, publish sleek journals and newspapers, and permeate social media.