May 3, 2023

David Dault: We’re delighted today to welcome to the show Charles Marsh, a professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia and director of the Project on Lived Theology. Charles is the author of many books, including God’s Long Summer, which won the 1998 Grawemeyer Award in Religion, and the acclaimed biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Strange Glory, a Pen Award finalist. He is also the recipient of awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the American Academy in Berlin, and the Lilly Endowment.

Today we’re talking about his recent memoir, Evangelical Anxiety. Professor Marsh, welcome to “Things Not Seen”.

Charles Marsh: Thank you, David. It’s a pleasure to be here. Thanks for the invitation.

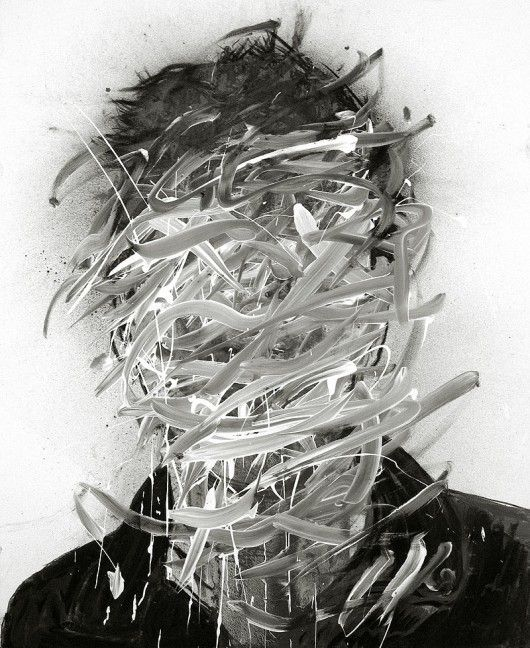

Dault: I am not sure what I was expecting when I first opened the book; there are a lot of things going on just on the cover.

First of all, there’s the picture of you in a kind of Peter Gabriel third or fourth album style. Your face has been erased and smudged out, and so there’s this blotch where a face should be. And, then we get these two words juxtaposed: ‘evangelical’ and ‘anxiety.’ Before we dig into the book, I’d like to start there. If you’d be willing to explain to my listeners when they encounter this cover, what you hope you are doing, either in orienting them or disorienting them towards what is to come within the pages.

Marsh: Ha, yeah. We worked a long time on that cover. It went through no fewer than 50 designs. I discovered a really interesting study by a New York based photographer on anxiety. There was one photo in which his head is exploding into fine black ribbons in a way I thought captured the anxious mind, so we played with different images of my headshot to achieve that effect and to signal that this is not a self-help book. It’s not a book that, at least initially, offers a set of guidelines or comfortable words to bring the anxious evangelical to a sense of God’s calming presence. It’s my story, but also, of course, a story that would not be at all unfamiliar to many evangelicals. The cover is meant to represent a subculture.

The words evangelical and anxiety are twinned in response to this image of self and mind. Evangelical anxiety is a weight and a dizziness, especially as it exists as a messianic summons of the Christian God in the practices of white evangelicalism. It is unbridled narcissism, but it’s also terror, configured around a sense of specialness: the specialness that comes with the feeling of having been chosen by God to serve on the front lines of the great cultural and cosmic struggles of the age; the specialness that comes from the feeling that you belong to the last remnant of Christian civilization in the evening land of our nation and world. Every moment is overcharged with meaning.

I’ve spent much of my scholarly and writerly life reckoning with the racial contradictions in white American evangelical witness. But this work is incomplete until we look more carefully at how many of our ideas, ideals, and convictions disfigure the interior life. A line runs directly from the interior to the social and political. I think we would learn about the toxic repercussions of the evangelical anxiety—we would accomplish more—if we took a more cautious, clinical approach to the problem. This requires empathy, of course, which does not seem to be a virtue in demand.

I’d like to say this too—and this is a long answer—but I’ll just say this before we move on: I hope to have written a book that has a kind of gentleness and humor and artfulness in its unfolding. I never thought I would be writing a book in the genre of neurotica. I don’t particularly enjoy reading books about mental health and mental illness. I find that often such books, memoirs in particular, are written with a kind of bravado, you know, a sense of ‘I am so messed up, you wouldn’t believe, and by the time you finish this book, you’re gonna be there with me in the mire.’ There’s also sometimes an insensitivity to language. People who are inclined or vulnerable to mental illnesses of various sorts know how important language is and how certain words—and this is particularly true within evangelical cultures—can really open up deep wounds.

I want to look with unflinching honesty at the anxious, tormented aspects of white evangelicalism and particularly its psychological shape and its fear, if you will, of the psyche. But I wanted to do it in a way that creates a kind of trust with the reader. I wanted to signal early on in the memoir that some pretty brutal scenes are coming, but I’m going to be okay and you can borrow from me if you need, and this journey will take courage, and there will be sometimes when we wonder if there’s even any reason to keep our hope in the risen Christ. That’s the kind of axis on which our lives and our imaginations turn. I’ll say yes, we will get there, and I just hope that kind of gentleness and trust comes through as well.

Dault: Well, in that answer you gave us a lot of pieces that I’m going to be digging into as we continue our conversation. One thing that really rang out to me was that you were not interested in creating a kind of spectacle or centerpiece of your anxiety or the breakdown that really is a lodestone moment here. What intrigued me in reading your book, Evangelical Anxiety, was how little there was of that. It shows up as a lightning strike moment, and otherwise it’s just gray clouds in the distance; a sort of squall line that’s always there but is not necessarily always fully present. And frankly, that surprised me. I’m wondering, am I reading the book in the way that you really hoped a reader would, where we’re not centering that kind of anxious narrative, but rather it’s more sort of a specter in the background?

Marsh: I am deeply gratified by your reading the memoir in that fashion. That’s so very helpful and encouraging. That episode of the breakdown in divinity school that you mentioned was at times much longer in other drafts, shorter insome drafts. It was the fourth or fifth chapter. It did seem in the end that it needed to come earlier in the book, but it didn’t need to be the first thing. The first scene is a kind of a dark, 500-word episode involving a worship service at a contemporary church and a feeling triggered by the sermon and rushing home to have my little personal communion with a five milligram lorazepam in front of the mirror in my house. And I think that is, David, the way you just framed this, exactly the way I wanted that primal scene, if you will, to stand in relation to the rest of the book.

There is a lot in the rest of the narrative—certainly in the 50 or 70 pages that follow—that seeks to explicate that event or to pose that event as a question mark. You get blindsided and undone by this acute anxiety episode in this first semester in divinity school with all of the terrors and torments that it brought with it. Why did this happen? I had lived and pursued this goal of being an evangelical thinker and using my gifts, whatever they were, and reading and writing and thinking and talking about ideas as a way to serve Christ, bearing witness in the secular academy and the public square and these places where we were excluded and historically persecuted. Our persecution complex really has no limits and continues in all kinds of exotic forms to this day. But the promise was that I would prepare for this, I would dig deep in the Word, I would arrange my priorities in ways that maximized my chance of conforming to the mind of Christ. I mean, I was taking on the mind of Christ with all of my energies and with my visions about my vocation. The opposite should have happened, right? Instead, I was undone.

At that point, I try to live into my southern literary roots and tell interesting stories and develop the narrative that pulls the reader through; one that is haunted, and that never forgets all of that dark storm, but does not luxuriate in the storm, as I think so many memoirs of this type do. They’re unrelenting. It’s like, we get it, you’re depressed or anxious, I understand. But as a reader, I can only bear your sorrow and suffering so much. I need to encounter the elements of writing and narrative that endear me to a text; characters and stories and humor and the color of life.

Dault: Well, and if I may, as we’re moving towards our first break, it really strikes me that if I were to give a one sentence logline for your book, Evangelical Anxiety, how I would characterize it is: this is Charles Marsh learning to fall in love again with his own body, learning to be at home in his own self. Now these are my words, not yours, but when I say that to you, does that feel right? Or would you say no, the focus is really somewhere else in summing up the grand sweep of this book?

Marsh: That’s really such a perceptive insight. It is the body that emerged for me in my evangelical pubescence with such alarm that it had to be made an object of deep spiritual concern. And everything that I listen to in sermons and Bible studies and my daily devotionals and my King James version Thompson chain reference edition said that my best way of navigating these very natural and beautiful changes was to distrust the mold to the point in which the body, my body, became not only a sight of distrust, my genitalia became a place that was so overcharged with meaning as to almost form a kind of ongoing and never-ending metaphysical struggle upon which everything depended: my inner integrity, my relationship with God, with my parents, with my friends.

The incarnation, of course, is a central narrative in which Christians form this kind of deep commitment to the earthly and the material and the bodily. While psychotherapy and psychoanalysis were very much a part of the clinical methodology that enabled me to develop this new narrative, it really was about living more deeply and in a much more embodied way into a doctrine of creation.

Dault: Well, in the first segment you were talking about your upbringing and how a person with a certain evangelical worldview growing up was convinced that if they did everything right, if they kept themselves morally and physically pure, that they would have no anxiety and that nothing would go wrong. I was mindful, as you were recounting that, of the typology developed by Walter Brueggemann in his analysis of the Psalms where he says that some of the Psalms are about orientation, some are about disorientation, and some are about reorientation.

Psalm 1 is a great example of orientation. If you live a moral life, God will bring you blessing and increase. If you live an immoral life, God will strike you down and will cut you early and fast. And then disorientation reverses that and says, ‘We did everything right and yet we’re being cut down early and fast. What is going on?’ I’m hearing in your own description of your experience, a kind of disorientation, and I’m wondering about the grounding of the reorientation. You’ve touched on this a little bit. You said some psychoanalysis, some therapy, but also, I get a sense that in your book, Evangelical Anxiety, you’re not going to put tremendous stock in these techniques to really deliver reorientation. And maybe it comes from somewhere else, but I’d love to hear more about that.

Marsh: Yeah, that’s interesting, and it reminds me of how much I feel having written this book, I want to become a a student of the Bible. Again, I know that sounds a bit dated, my biblical literacy, which was considerable, peaked when I was 12 years old. And I grew up just deeply immersed in the biblical mythos or imaginary. I have memories of our first home in Mobile. My father was a Southern Baptist minister at a church there, of blue-collar folks who worked in shipping and various aspects of industry related to the bay and to the military, and being called out at dinner parties from my room to tell stories of the Bible, which I would apparently deliver with great dramatic swear. And during my five years in public school in Mississippi where we moved when I was 10 or 11—despite the fact that, you know, Mississippi is a little Ireland and it continues to produce, at a disproportionate rate, some of the most talented writers in the world (and this keeps happening in the new generation as well)—I don’t recall having been assigned a novel or a book, but I read the Bible deeply and immersively. I should also add that I was the sword drill champion of Jones County, Mississippi. I’m sure you have no idea what the sword drill is, but suffice it to say, yeah.

Dault: Why don’t you tell our listeners quickly what a sword drill is?

Marsh: Well, it involves a group of children or young people in a friendly competition (though in the deep South, I don’t know that there’s any competition that’s friendly), standing in a line, seeing who can find a passage in the Bible the quickest. The leader will say, 2 Corinthians 5:10, and you take your Bible—your sword, the sword of the Lord—and you find the verse and you open it, put your hand on it, and take a step forward. It doesn’t signal theological sophistication or really anything about the knowledge of the text at hand, but I knew my way around scripture, and I actually had vast passages memorized that I still use. But I feel like, you know… here’s something I wanted to introduce that may give that little preamble some context.

I do feel that part of the evangelical anxiety that I suffered and lived with and have tried to reckon with and to find a way out of has a traumatic form and that there are theological lessons that a very young child in this ethos learns compulsively, like the psychic sense that one finds associated with trauma.

So as I felt such brutal notions of an eternity in hell as part of my daily mental operations, along with this kind of overcharged desire to find God’s word and eschatological meaning, and every experience, that everydayness, the mundane, are not parts of that evangelical cosmos, so that the Bible and my relationship with the Bible and my trust of the Bible also suffered.

I would say two things in response to the question that the reorientation did require, without any reservation: the tools and gifts and skills of an empathetic and gifted psychiatrist or psychotherapist or psychoanalyst, as well as, in important times, psychopharmacology. But, it was unlike Sigmund Freud’s account of the way this is supposed to work, as he questions it out in his little book, Future of an Illusion: the kind of confidence that this man or woman cured of his or her neurotic unhappiness in the analytic dialogue more broadly, more eclectically through the use of medications and the like, will then somehow emerge as a fully autonomous person able to live in this new education to reality alone. A reality, which of course, is governed by a scientific paradigm.

Now I think first, those notions of the therapeutic work are dated – in the fields of psychotherapy, counseling and psychiatry, but psychoanalysis as well. There are many people of faith in these fields. There are really different ways of understanding the relationship between the difficult psychological work that you need in this reorientation and the difficult theological and spiritual work that you need. And for me, one of the traits that was born out was similar to what was noted by philosopher Paul Ricoeur (who wrote this really interesting book on Freud that has a kind of Barthian focus in its appreciation, but it is a sort of theological overcoming of some of the Freudian eporials in its understanding of religion, Christianity in particular): there was a place beyond the critical mind.

There’s the naive, there’s the critical. The naive is the state of mind in which we believe in these doctrines of the church and the mysteries and all of this, with this kind of direct, literalistic kind of vigor. And in the critical or reflective, whether you’re reading philosophy or psychoanalysis, all of that becomes a kind of question that has to be understood with attention to the meaning of these doctrines, of these ideas, so they don’t have their own intrinsic truthfulness, but they need to give way to expressions—whether it’s the infinite value of the human species or it’s some kind of range of symptoms and their meanings. But there’s also this tense critical moment, which I think Freud and most of the secular psychoanalysts and therapists completely miss. And in missing that, they also fail to recognize the heuristic value of therapy to cleanse the psyche of false constructions of God, of idolatry, of images of God that have been formed around our cultural preferences and prejudices, around class and value.

I think that I didn’t know what was going to happen when I went into psychoanalysis, to use that example, of my theological thought, of my way of thinking about myself in the world in relationship to creation and others and life, and that the therapeutic and the theological have a mutually enriching kind of power and role in this reorientation process.

Dault: I’m struck by what you just said about your reorientation process being a process that drives you back into the texts of the Bible, and you mentioned peaking in your reading of the Bible around when you were 12. But there’s this point in your book, Evangelical Anxiety, where you are referencing a favorite volume of a theologian by the name of Karl Barth. It’s a book called The Word of God and the Word of Man. And I’m recalling that there’s an essay in that book called “The Strange New World that We Encounter in the Bible.” And part of Bart’s thesis is that we’re constantly in tension—and he’s certainly not the only one to bring out this idea—between trying to drag the Bible closer to the world that we know or allowing ourselves to be dragged more towards this alien strange world that the Bible beckons us to. And I’m wondering, as we’re talking about this process of reorientation, do you feel like you are being drawn more towards the legible, the familiar, the known in the shared world that we have? Or do you feel like reorientation is drawing you more towards something new and perhaps a little alien and perhaps wonderful in all senses of that word?

Marsh: Yes, I appreciate your mentioning Barth, The Word of God and the Word of Man. It’s a book that I teach, and it’s a book that I come back to that is endlessly giving in its power and surprise and delight.

I think there is a very strong parallel between the God of Jesus Christ as so rendered in those essays, and other essays of that period, and the God that emerges in the course of therapeutic work that requires the disentangling of our images of God from their finite sorts of references that have emerged because of family, through tradition, through culture. These essays are just like prose-psalms on speed, of the God who comes to humanity from the far country, from the far away country of the triune God, who calls us into the strange new world, who stands over our finite loyalties and our unceasing production of the false God, both in judgment and in grace.

This idea that the kinds of gods who we associate with distrust of the body, of suspicion, of worldly love, suspicion of life and the richness of human experience, these become, for Barth, finite ways of speaking about God. All of those stunning passages we find in Barth that expressed this, what you call this sense of newness and the sense of novelty and I would say a sense of wonder and a kind of reimagined mystery, I find that to be true of where I am today. And I do hope that these little vignettes that you find in Evangelical Anxiety—vignettes is a quaint word, they’re more languorousdispatches from my ordinary going about things—that those are also seen as these little spaces of discovering mystery in the quotidian. I think that it’s difficult for someone who was born with all of these world-shaping mandates of the evangelical ethos to let go of that messianic impulse and just be present in a moment. Then trust, right? Trust God, trust yourself, trust the languorous—or it could be even chaotic or unexpected—kind of activity of life. All of that is about newness and mystery, and it’s about living into our material and mortal lives.

Dault: If I can pick up on something that you just said, and it’s a word that has come up a couple of times in our conversation so far, it’s this word, quotidian: gesturing towards the everyday, the ordinary. You have foregrounded in this book that you’re a person who has lived most of your life with various forms of anxiety disorders. Longtime listeners to the show will know that I also am a person who lives with those realities, and it’s been my experience that living with anxiety, living with depression, living with a non-neurotypical way of being in the world renders the everyday anything but every-day. So, sometimes the ordinary can be extraordinary in its ability to trigger or to cause fear or anxiousness. So, I wonder as we’re moving towards our next break, about the tension between the fact that everyday quotidian implies a certain routine, a certain expectation, versus the fact that for a person who is coming to the world with an anxiety disorder or some other form of mental illness, the world is never quite every-day.

Marsh. Yes. To grow calm in an evening is such a gift. And to feel that sense of a presence that is enough in itself, takes some getting used to. Anxiety is this constricting force, but it also throws us out of those capacities to be still and present in a moment. I don’t want to presume or say that I somehow have moved now fully into this era of equanimity and repose. Anyone who knows me would say otherwise. But I think the healing that comes through the sources that you’ve described and the ones that I’m recalling illuminates that kind of place of repose and calm, and it makes it possible to be in there a while, because it relieves us of the burden—I’ll say this more personally—the burden to just make every moment, every occasion, a moment or occasion of eternal consequence.

But that’s the kind of habituation that is so easily formed. I think of the journey of being relieved not only by the therapists, by the analysts, by ourselves, but also by God, and just reading scripture truthfully that God does not want us to live as emissaries of self-righteousness in the world, seeking to impose our own agendas on everything different. There’s a sense of participation and gift in being still in the tabernacle and in all of these images that are much more pervasive in shaping the life of faith lived in view of this God who comes to us from the faraway country. They give us the opportunity to be still and to slow down and to see that our own attempt to control all the situations throughout our own nervous management are themselves idolatrous constructions that we had best expire both for theological but also for good psychic reasons.

Dault: Well, you are a person who has spent your life in academia. I am also a person who has come in and out of academia in addition to being a radio guy and the other hats that I’ve worn throughout my career. But something that I’m very conscious of and was very conscious of reading your book, Evangelical Anxiety, is (and as we said in the last segment) you’re a person who is now speaking publicly about mental illness. I am speaking publicly about mental illness, but there was a period in my career during my first trajectory in the tenure track where these things began to first rear their heads. And I felt like I couldn’t tell anyone. I really want to ask you a question about masking, and what it is to know about yourself that something isn’t working but feel like you have to hide it from everyone around you—that somehow if you were to mention it or to acknowledge it publicly, that maybe the sky would fall. In addition to that, I want to ask about the exacerbating effect of these kinds of evangelical narratives that you’ve talked about through our conversation. So, let’s first just start with that question of masking. What was that like for you when you were experiencing the first blushes of this and feeling like ‘maybe I can’t tell anybody?’

Marsh: Masking and finding yourself both battered and broken by these debilitating symptoms, but also unable and unwilling to say anything to anyone because . . . well, there are different reasons for that: because you would be exposing your own vulnerability, you would be perhaps disappointing the other who you imagine having idealized you in some way as a Christian. In the experience of my first major anxiety episode and the weeks and months that followed, I wasn’t even aware of wanting to protect myself from exposing or from sharing or telling another person about the torment and terror that I was experiencing. I mean, I’d been raised, of course, with a kind of constitutionalsuspicion of not only psychiatry but psychology as a broadly conceived discipline and form of healthcare. Evangelicals were people who had been redeemed by the blood of Christ, and the Holy Spirit indwelled our lives. And having the ultimate healer present twenty-four seven to call upon, we were ‘too blessed to be stressed,’ as some might say. We were not the kind of people who needed the work of psychology; and more, the work of psychology could do things to us that could even further endanger our relationship with God.

And I was then thrown back on the only explanations that I could muster of why I was battered and bruised by these unrelenting anxiety symptoms. I thought these must be a trial or maybe even a gift.

Some of the devotional books I read—Oswald Chambers, My Utmost For His Highest, for example—really encouraged me to bear down on that thought, to take joy in my torment, and to feel like only in my unmaking and my disintegration as a Self, could I then be filled with God’s mercy and so forth. That didn’t work out well at all. I became deeply immersed in medieval mysticism, and I found some consolation there.

The sort of quasi-radical, Meister Eckhart and The Cloud of Unknowing, too, was a very important book for me. It was a consolation in discovering this cloud of witnesses, this cast of Christians that were not part of my evangelical canon and who accepted suffering, who found mental torment and sought to live into it in some way. It was more the consolation of fellow travelers than ideas and strategies of contemplative life—lives that enabled me to feel better psychologically.

There’s a lot to be said about consolation. But in any case, it was years, not just months, but years before I could even recognize that I had been masking. I felt that the torment that had overwhelmed me was either something deserving, like it was a gift I needed to bear down deeper in the Word, or it needed to be fared out through some taking of spiritual inventory and finding the places in my life that maybe were deficient, that needed further nourishment, so that I wouldn’t have these anxiety symptoms.

“I attributed it entirely to myself, but not as a consciously masking response, rather as a response that—I mean, there’s also a lot of narcissism implicit in (tragically or sadly) some kinds of mental illnesses, but I really believed naively, even though I’d read some psychology (I taught Freud and others)—that I was just a singular case that no one else had. I was just messed up in ways that no one had ever been, ever. It was just me. It was just because of something about my blistered, poisoned soul that I had to bear solo as long as I could. It’s amazing. I made it, you know, seven or eight years, and there were times when the symptoms eased and became more manageable. But I lived within this kind of ambient world of expectation: of expecting, of seeing, of fearing the terrors, of having no understanding of them, no control over them.

“And I think the day one Spring—I was working on my doctoral dissertation, and a lot of the symptoms had resurfaced with this new kind of intensity and my not really knowing what would follow—I thought, ‘Okay, I have no other recourse now, but to just walk in to student mental health and say, “I need help,”’ which is what I did. I threw myself at the mercy of the University of Virginia student health and mental health center. And what was so remarkable was, first of all, getting some medication that acted on my central nervous system and actually healed the biochemical, and then calming as a result.

As a kind of heuristic exercise alone, this was helpful. ‘Oh, I can feel this way.’ This kind of wretched, this sort ofoverdrive that I had been living in, that had not just mental but physical expressions, can be relieved. Again, beginning to talk, and to slowly and with some hesitation enumerate the various symptoms, the very physical symptoms that were part of my anxiety disorder, and to see that while those fit into a very familiar pattern, these symptoms are the result of other ideas, other states of affairs. These symptoms have explanations, these symptoms have causes; we can read them as you read a book.

And the idea that these symptoms could be encountered and looked at as potent little texts was so extraordinarily helpful because then they opened onto other more fundamental or more determinative experiences, and they became interlinked in narrative form.

It wasn’t first the awareness that I’ve been wearing this mask for seven or eight years, but it was this sort of sadness—like the sadness that you feel when you look back on yourself with love. Maybe you see yourself as a photograph of yourself as a child in a moment that you know was one of awkwardness or fear, and you just want to tell that person: ‘Hey, you can be okay. I can see, I can recognize in your eyes that glint of terror, but we’re going to get through this, and we’re going to figure this out. You’re going to be okay.’ And it was more of a sense of that kind of sadness that I think is born of compassion. To some religious traditions, it may sound incomprehensible. I know when I was trying to describe to my analyst I saw in Baltimore who was an observant Jew, when I tried to describe to him that evangelical ritual of breaking the will of the child, he took a step back and he said, ‘Right Charles, I’m just going to need you to explain that to me because I do not understand this idea.’

To some it seems incomprehensible that you and I might find it a great achievement and a grace to be able to look at ourselves with compassion and to think of ourselves compassionately and to love ourselves.

Looking back on that, it was masking of a grand sort. I just wish that our churches had not just allowed us but required us to be unmasked. I think it would completely re-revolutionize our understanding of life with God. Then we may say, as Bonhoeffer said in prison when he was confessing to Eberhard [Bethge] that he could no longer read the New Testament, that he was only reading the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible, and had come to this sort of great and joyous realization that God not only called sinners and murderers and thieves to accomplish his purposes, but there was also a kind of glory in their simpleness. That’s the way it should be: that there’s going to be a church, a place, a space of worship beyond the sort of wasteland of post-ecclesia, post-Christian America. It’s going to have to be places that not just accept but embrace and affirm us in our deepest brokenness.

Dault: It strikes me that writing a book like this, your book, Evangelical Anxiety, is an act of trust. You’re handing this to the reader and you’re saying, ‘These vignettes are part of my story, and I want you to bear this story with me.’ But it’s also, it strikes me, an act of hope that you are putting it into the world in the hope that there will be some kind of response.

As a way of moving towards the end of our conversation, I’m wondering, as you are now looking back on the book having been released, is it meeting your hopes? Is this act of trust creating what you hoped would happen in the world? Or is there still more that you hope will come?

Marsh: I did write the book with that hope. It’s a chastened hope. I mean, it’s a hope that—at least with attention to the evangelical culture that nurtured me and nourished me as a child and young man—is held with realism, if not some skepticism. I wrote the book with a commitment or with the hope to try to go as far as I could in understanding and excavating the sources of my evangelical anxiety, despite how revelatory or intimate or humiliating or shameful they might be. In doing that, I’m aware that that’s not the way Christians by and large write autobiography. In addition to the Bible, I should have said as a child I did read a lot of missionary autobiographies or autobiographies by some of the great evangelical saints like David Wilkerson, Crossing the Switch Blade, Border of Yale. Any time men of God did great things and wrote stories about them or people wrote stories and biographies about them, these books found their way into my bedroom, into my library.

But even in the recent years, with only a few exceptions, no evangelicals seem willing to look at issues of race and sexuality and mental health. Anne Heche, the actress who died sadly just recently, her sister was a very talented writer named Susan Bergman who has sadly been left out of all the obituaries I’ve read.

Susan Bergman taught at Wheaton College as an adjunct professor during the years when she was writing a memoir that in my mind represents one of the most beautiful, daring, heartbreaking, and courageous memoirs that any evangelical has written.

It’s also beautifully written. She was writing a novel in the years after the memoir was published and died of cancer. Her book Anonymity is a memoir of her life, of her father, who was an evangelical music of minister who was also living a double life as a gay man in New York City in the seventies and eighties. He was one of the first casualties of the AIDS epidemic. It’s one in which she’s looking at her father’s duplicity and the repercussions of his duplicity on her family. In the course of writing, she inevitably and inescapably was led to confront her own duplicity. The power and the courage and the honesty of Susan Bergman’s memoir maybe helped create a larger space within which these inescapable and essential conversations need to happen. The hope I have is that I’ve given voice to my own story in a way that encourages others to give voice to theirs.

Dault: Well, Charles Marsh, I want to say, as a reader of your book, I did feel encouraged. I did feel as if I was being invited in, not to a rehearsal of sadness or rehearsal of spectacle, but rather into a flow of a life that is trying to grapple with some aspects of the unknown and build back towards something better in hope. I’m so grateful that you took the time to put these words on paper, to reflect on your experiences, and to shepherd these anxieties in the way that you have. But I’m especially grateful that you took the time today to talk about it with me and my listeners.

Marsh: David, it’s been a pleasure. I appreciate your attention to the book and the detail of your questions. I hope it’s helpful to your listeners. I feel like I’ve learned new things about the book. So, thank you.

Adapted from Podcast Things Not Seen: Conversations About Culture and Faith, October 2, 2022

Transcript edited by Kristopher Norris, author of Witnessing Whiteness: Confronting White Supremacy in the American Church (2020). He has served as a pastor and seminary professor in Christian ethics and now directs The Shalom Project, an anti-poverty nonprofit in North Carolina.

Charles Marsh is a Commonwealth Professor of Religious Studies professor and director of the Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia. He is the author of numerous books, including God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights, which won the 1998 Grawemeyer Award in Religion, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a PEN award finalist, and most recently, Evangelical Anxiety: A Memoir. He lives with his wife Karen Wright Marsh in Charlottesville, Virginia.

David Dault is a writer, media professional, and educator. He is the host and executive producer of Things Not Seen: Conversations About Culture and Faith, an award-winning radio show and podcast. David has a PhD in religion from Vanderbilt, and a masters degree from Columbia Theological Seminary. When he began Things Not Seen, he was teaching in the religion department of a liberal arts college in Memphis. He is currently a Visiting Scholar for theology and media at the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago.