July 6, 2023

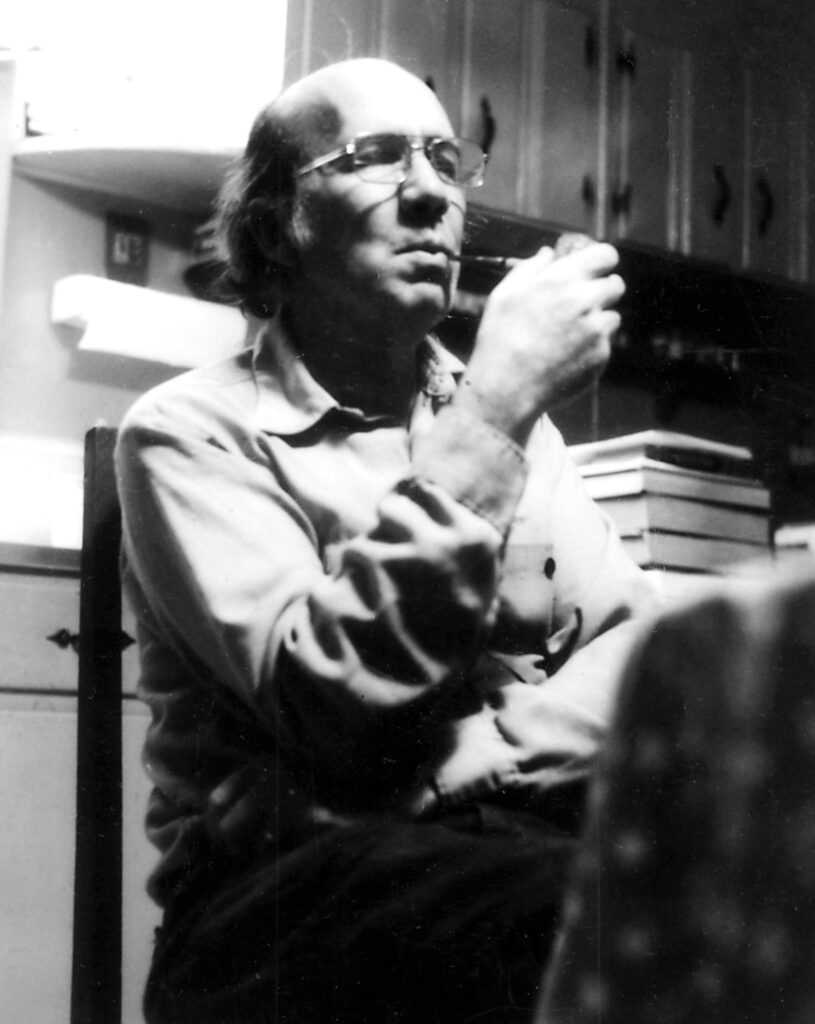

Thirty years ago today, on July 6, 1993, I paid a visit to the Baptist preacher, civil rights activist, and writer, Will D. Campbell on his small farm outside Nashville.

We sat on the porch of his Tennessee writing shack and shucked corn, while he talked about his years as a Christian dissident in the segregated South and about what it meant then and now to live as “ambassadors of reconciliation.”

Campbell was born in 1924 into a dirt-poor family in Amite County, Mississippi, educated at Yale Divinity School, and ordained for the ministry in the Southern Baptist Convention. A fondness for bourbon whisky, scatological language, and the radical orthodoxy of Karl Barth made him no more at home in the culturally conservative denomination than as a poor white Southerner among the tweedy seminarians of Yale.

Over the years, Campbell would manage to infuriate just about every white evangelical in and outside of the South, starting with his book Race and the Renewal of the Church, published in 1962, in which he argued that the new identity of the Christian was one of complete and incontestable equality in Christ.

In Will’s reading of the apostle Paul, being Christian meant joining a new family, “a tertium genus, a third race—a people neither Jew nor Greek, bond nor free, embracing master and slave alike, king and liege.” Racism has its roots in the sin of idolatry.

Campbell pushed the matter hard. Not only is membership in the Ku Klux Klan a betrayal of the gospel—most mainline white Christians would have had no trouble with that charge. The Klan could be dismissed as white trash and an embarrassment to the decent southern evangelical. But membership in exclusive societies is equally a betrayal of the gospel. As a third race, a new people, Christians will need to renounce membership in groups and organizations that separate by income, education, skin color, or cultural privilege.

Years later, amidst much discussion in the early 1980s of the resurgence of white racist organizations in the United States, Campbell would warn liberals not to miss the bigger picture. “Let’s talk about . . . the Ku Klux Klan,” he said, “but let’s do it in the context of the resurgence of Exxon and J. P. Stevens, and the resurgence of the Nashville’s Belle Meade Country Club.” Attempts to cling to the old ideal in any of its forms were a “living denial” of “the message of reconciliation entrusted to us.”

He recalled one especially contentious meeting with white southern ministers in Atlanta during the civil rights years. Campbell knew the men were disturbed by his application of the New Testament to southern race relations. But not wanting to address the race issue directly, one of the pastors said he would like to know a little more about Campbell’s theology. He may have even said he was concerned about Campbell’s hermeneutics.

Campbell had just spent the better part of an hour telling them what he believed, so he cut to the chase.

“My name is Will D. Campbell. I am who my momma and daddy named me the night I was born. I live in Tennessee. I have three children. I am a preacher of the good news of Jesus Christ. I believe God poured his love out for us in Jesus Christ, reconciled the world to himself, saved us from our sins. But I know why you’re asking where I went to school. If I had gone to Bob Jones, that would mean one thing. If I went to the Presbyterian seminary, you’d think you’d know what that means. If I went to New Orleans Baptist Seminary, or Harvard, or Princeton, right away you’d think you’d know who I was. But the words are very clear in the scriptures. Once a man has truly seen the truth it doesn’t matter where he’s from, what his race is, or where he went to school. None of that matters.”

“I believe God was in Christ, not maybe and not perhaps, not just if we’re good boys and girls, but God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself. That means it’s over and done with. Our salvation is accomplished. We are one people. We have been reconciled to God and to each other. And so racial prejudice is a violation of that fact. Nations are a violation; classes are a violation; joining the Country Club is a violation. I believe God was in Jesus Christ. Goddammit, that’s what I believe!”

After 1965, Campbell scandalized many in the movement when he announced that the same concern that they had shown to the disenfranchised minority should be shown to poor whites – and to segregationists and racists. Many of these men and women, who were unsettled by the prospects of legal equality for blacks, had been abused as children and were tormented by fears and uncontrollable rage, often by untreated mental illness. Campbell made himself available as pastor and confessor to racists and to members of the Ku Klux Klan, seeking to share gospel-grace with outcasts and sinners.

“Most of us suspect that if Christ came back today he would once again be born among the lowly,” he explained. “But wouldn’t it shake us up if he came today and was born into a Klan family!”

The redneck racist needed to be loved and cared for. Such was the radical love of Christ, the spirit of agape. Only a few people knew of Campbell’s pastoral relationship with the Klansman, which lasted until his death in Parchman Prison on November 5, 2006.

In August of 1998, Campbell traveled to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for the trial of Sam Bowers. Bowers was the former Imperial Wizard of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan of Mississippi, who reigned over the most violent white terrorist organization in the South. He orchestrated the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, which riveted the nation and brought massive media attention to the state’s brutal racism; in 1998, more than thirty years after his first arrest, Bowers was convicted for the 1966 murder of Vernon Dahmer, an NAACP leader, land owner, and churchman in Forrest County, Mississippi. Campbell had been introduced to Bowers in the time of his impending arrest, when Bowers was still living in the nearby town of Laurel, running a pinball machine company and writing tracts on politics and religion. On the first day of the trial, Campbell arrived early in the Hattiesburg courthouse and approached Bowers, who was sitting at the defendant’s table, and shook his hand. Bowers asked the minister to take a seat but Campbell declined. Campbell then walked across the room, greeted the Dahmer family, and took a seat with them, where he remained for the rest of the day.

During a recess in the trial, a newspaper reporter asked Campbell how it was possible for him to walk between the grieving family and the Klan terrorist, who surely deserved punishment, not compassion. Campbell’s actions seemed offensive to the reporter. Did he really think Bowers deserved his kindness?

Most newspaper coverage had portrayed Bowers as a monster, the embodiment of pure evil. The Southern Baptist preacher adjusted his black frame glasses and offered an explanation to the Boston journalist, a variation on his earlier “This I Believe” speech, an updated testimonial of his strange vocation. Why had he acknowledged Sam Bowers with a handshake?

“It’s because I’m a goddamned Christian,” he told a gaggle of reporters. He would be sitting with the Dahmer family, but as a minister of the gospel, he would not forsake Sam Bowers, even though the former Imperial Wizard was wholly undeserving of such love.

The last time I talked to Will, I asked him if he was still preaching at the little church near his farm in Mount Joliette, Tennessee. He drawled out a “no” and said he had long gotten tired of the “steeple.” Besides, he added, the standing invitation to preach had been withdrawn, a result no doubt of some contrary remark, though I didn’t press for details.

When I asked Will where he was going to church, he told me he’d decided to become a “seventh day horizontalist,” and we both laughed. He had earned the sabbatical from “the sanctuary and the steeple”.

Let us teach our children the story of Will Campbell and all the other Jesus-loving misfits, oddballs, and malcontents who rub against the grain. For it will surely not be the court prophets, patriot preachers, and right-wing megalomaniacs whose stories the church will tell young people as exemplars of authentic faith. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once said that Christians must sing more beautiful songs before he would believe in their redeemer. We will need to sing more beautiful songs to our children and to the world.

Charles Marsh, July 6, 2023

(Adapted from Wayward Christian Soldiers: Freeing the Gospel from Political Captivity, Oxford University Press, 2007)