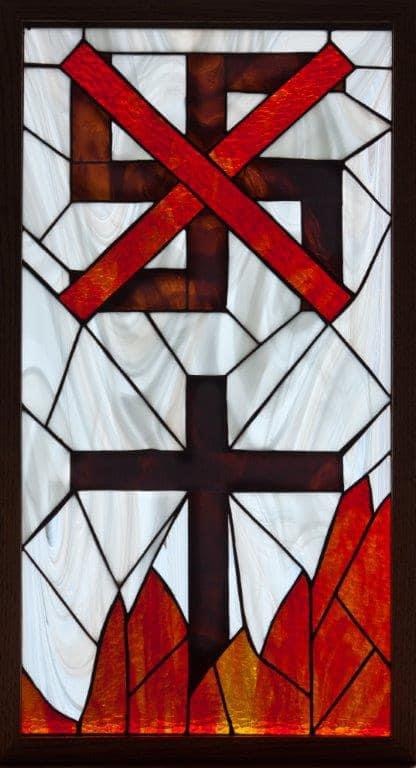

“I am the Way and the Truth and the Life; no one comes to the Father except through me.” John 14:6

“Very truly, I tell you, anyone who does not enter the sheepfold through the gate but climbs in by another way is a thief and a bandit. I am the gate. Whoever enters by me will be saved.” John 10:1,9

“Jesus Christ, as he is attested to us in Holy Scripture, is the one Word of God whom we have to hear, and whom we have to trust and obey in life and in death.”

“We reject the false doctrine that the Church could and should recognize as a source of its proclamation, beyond and besides this one Word of God, yet other events, powers, historic figures and truths as God’s revelation.”

So begins the Barmen Confession, the call to theological resistance, drafted by Karl Barth, and issued in 1934 by dissident Protestant ministers and theologians – the emerging Confessing Church – in opposition to the German Christian’s embrace of the “Führer Principle” and the assimilation of the German Evangelical Church to the Nazi regime.

Since it was drafted ninety years ago the Barmen Confession, or Declaration, has served the Protestant world as an inspiring example of robust Christian conviction and courageous dissent – a ray of light in times when the church has become an appendage of the nation.

In his classic Creeds of the Churches: A Reader in Christian Doctrine from the Biblical to the Present, the scholar John H. Leith calls it “a witness, a battle cry.”

The London Times ran the full text on June 4, less than a week after the synod concluded, and translations soon followed in newspapers and church periodicals throughout western Europe and the English-speaking world.

The Barmen Declaration was in some ways just a forthright and single-minded affirmation of the Lordship of Jesus Christ according to scripture and tradition: “ ‘I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me.’ (John 14.6). ‘Truly, truly, I say to you, he who does not enter the sheepfold by the door, but climbs in by another way, that man is a thief and a robber.… I am the door; if anyone enters by me, he will be saved.’ (John 10:1, 9).” But it was also an exercise in subversive indirection. Reflecting on John 14:6, for instance, it says, “Jesus Christ, as he is attested to us in Holy Scripture, is the one Word of God whom we have to hear, and whom we have to trust and obey in life and in death. We reject the false doctrine that the Church could and should recognize as a source of its proclamation, beyond and besides this one Word of God, any other events, powers, historic figures and truths as God’s revelation.”

It was bold as far as it went. If Jesus is the one Word of God and Lord of all, then every political claim to bespeak God’s purposes is illegitimate, if not idolatrous. And, yet, the statement remained evasive on the most urgent concrete issues, never once mentioning the Aryan paragraph, just as years later the Confessing Church would demur on the burning of synagogues, the deportation of Jews and other non-Aryans to the concentration camps, or the extermination of people with physical or mental disabilities. At least, this was the estimation of Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Bonhoeffer skipped the conference in Barmen but signed the declaration. Still, even as he promoted the declaration to his ecumenical allies, he remained suspicious of many of his cosignatories.

In this recent exchange with award-winning filmmaker Martin Doblmeier, Charles Marsh discusses the Barmen Declaration and Bonhoeffer’s theological critique of its limits.