This summer the BJM team is learning how to exist in a place that is not our own. Back in June, the Well, our women’s center in the Tenderloin, was flooded. There was some pretty serious damage and we were told repairs would take at least through the end of the summer. However, thanks to the hospitality of some of our community partners, we have found other spaces that allow us to continue running all of our summer programs. Since the floors of our dance studio are currently being ripped up and replaced, our Thursday afternoon dance classes are being held in the community room of an apartment building on Turk Street.

There is a large Muslim population living in the Turk street apartments and many of the girls who attend dance class come from Muslim families. Thus, as Christians, we are entering a space that is truly not our own. As a staff, we’ve been discussing how to navigate this environment as Muslims and Christians come together. Dance classes normally begin with a short teaching illustrating a concept from the Christian faith. However, something that a few of the Muslim moms said caused us to pause, pray, and examine this practice. They told Karol, a BJM staff member, that the Christians that run these programs always have a hidden agenda. When Karol brought this up in staff meeting I couldn’t help but think, “Well… we do….”

I wondered if I was the only one thinking it. I know that everyone on staff is completely genuine. They all sincerely believe that the Gospel is the most important message that they could impart to these girls and that Jesus can do more for these girls than they ever could. And even though dance class is mostly about promoting a sense of self-worth and providing support for girls in a difficult neighborhood, none would deny that the end goal is for these girls to know Jesus.

As I sat there questioning the implications of this, someone spoke up and voiced my thoughts for me. “Well, we do kinda have an agenda” she said. A shrug passed around the room. How do we do this? If it is true that dance class is about more than creative expression, empowerment, or community support but is actually about sharing Jesus with the girls (in the long run), and this is precisely what the Muslim parents are jaded towards…. Then what do we do?

It saddened me to think that this was the most powerful association the Muslim mothers had made with Christians. The women had not one real Christian friend that did not later pull a bait and switch on them. So we discussed how to find common ground between our devotional topics and the Islamic faith. We decided to avoid back-and-forth comparison of any kind and instead to consider truths about God that the Muslim community would also appreciate. Someone suggested that we even make take-home cards describing the teaching for any parents that are skeptical, feeling that increased transparency could help engender trust. While these measures were all well received by the group, for some I believe they created tension between being respectful and suppressing BJM’s core values. The Gospel is at the heart of BJM, and staff members were hesitant to be any more reticent in their discussion of it. But in the end, we humbly accepted that we are in a place that is not our own and we must respect the experiences of the people whose space we are inhabiting. These women have felt that Christians always have ulterior motives; therefore we must bear the weight of that wrongdoing and the mistrust it has created. We must lament the beautiful potentiality of friendship that has been squandered and perhaps even the barriers to Christ that have been erected by Christians who have failed to love these Muslim women without conditions. And so we prayed. We prayed that we would recognize our hidden agendas and relinquish them. I prayed that the girls would know Jesus within the context of their Islamic world, and that no one would feel the need to take them out of it in order to make that happen.

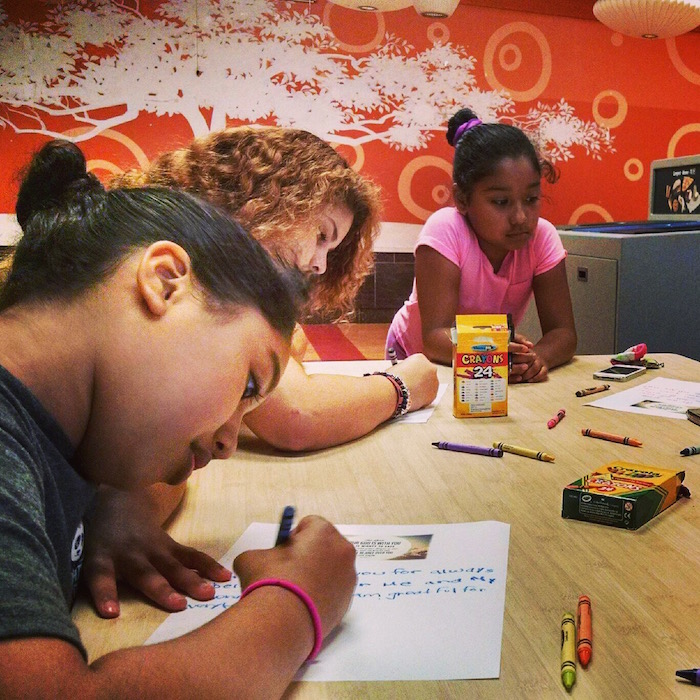

The next day came and it was time for another dance class teaching. We focused on Zephaniah 3:17, telling the girls that God “takes great delight in them” and that He “rejoices over them with singing.” Then, they were invited to write letters or draw pictures to God. The teacher gave an example of the kind of pictures she might draw for God. She imagines God as a “Papa God,” she said, with a big white beard and a staff like a shepherd. Although the shepherd is certainly a valuable, biblical rendering of God, as I looked around at the faces of the girls in the circle I couldn’t help but wonder, is this the only image of God that is presented to them? When they think of God, do they see a man? Do they see an old, white, bearded, Anglo-American man?

I sat down next to a little Muslim girl named Bria* who was struggling to put crayon to paper. A rather sheepish girl, she sat and stared at the blank page quietly while the girls around her scribbled furiously.

“What do you think God is like?” I asked.

“He’s…. a good guy,” she replied. I smiled.

“What do you see when you think of God?”

“…Clouds.”

“Okay, great! Why clouds?”

“Because… God is on top of us.” She meant above us. I smiled again.

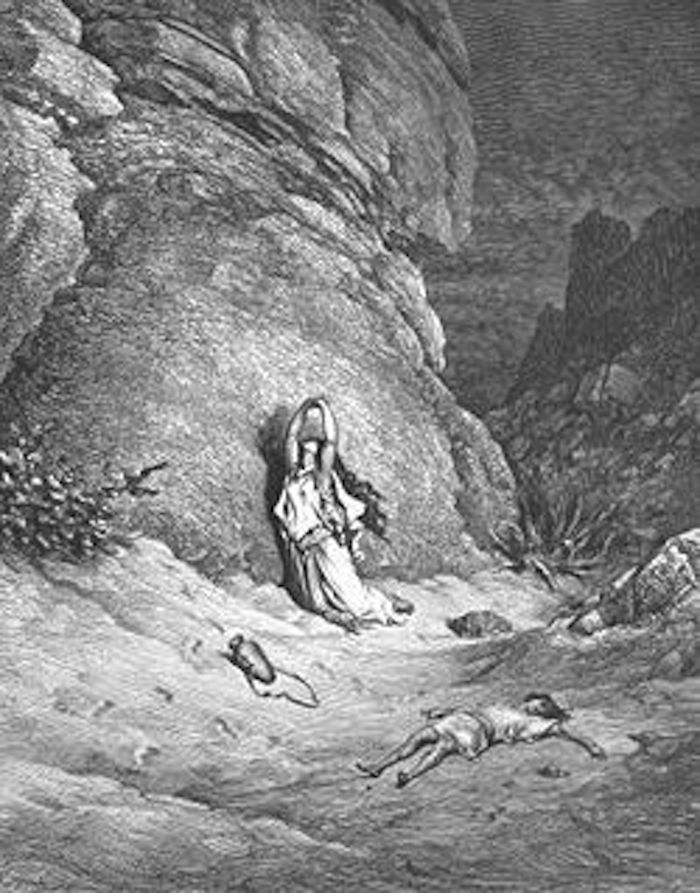

I encouraged her to draw what she saw. Perhaps her image of God is as nebulous as a cloud… and maybe that’s a good thing. If there is one thing I’ve learned in my short religious studies career it’s that a variety of images of God is necessary, and so is the element of mystery. For much of the Old Testament, the predominant image of God is the “God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” However, in Genesis 16, we are presented with another side of this same God. The God of Abraham, the God of the great patriarchs, appears to Hagar, a poor Egyptian slave woman serving as Sarah’s handmaiden. Sarah, in her impatience to receive the promised heir, forces Hagar to lie with her husband Abraham. After she conceives, Hagar flees her mistress’ abuse by running into the wilderness. It is there, in her most desperate hour, that she meets God. The angel of the Lord (understood to be a manifestation of God on earth) addresses her directly, by name, and allows her to speak for herself. Then, God tells her to return to her mistress, but with a promise remarkably similar to the one that God gave to Abraham: that her descendants would be too numerous to count. In response Hagar “gave this name to the Lord who spoke to her, ‘You are the one who sees me’” (Genesis 16:13).

Hagar saw God and felt seen by Him.

In her landmark work of womanist theology, Sisters in the Wilderness, Dolores Williams connects the story of Hagar, with which the black community has long identified, to black women’s experience of surrogacy/motherhood, oppression, and survival in the United States. She points out that Hagar is the only character in the entire Bible who has the privilege of naming God. When Hagar flees a second time, this time with her son Ishmael, God enables their survival by helping Hagar find water for her dying child, and “God was with the boy as he grew up” (Gen. 21:20). This God, Williams claims, is different from the “malestream” God of Abraham. She is different even from the God of black (male) liberation theology, who is always portrayed as the Great Liberator of the Exodus, in spite of stories like Hagar’s (in which God’s provision does not come in the form of liberation from slavery). Hagar’s God is not the God whose authority Sarah probably cited when she forced Hagar to be Abraham’s concubine. Hagar’s God is the one who sees her.

More than anything, I want the Muslim girls in dance class to encounter the God who sees them. This God might not look like “Papa God” or even the “Christian God” as we describe Him. I later heard that two of our girls (who did a similar activity in another one of our dance classes) wouldn’t stop writing letters to God all week long. They were told to write just one, but, as their older sister reported, they didn’t stop there. When I heard this my heart leapt. By writing these letters to God they are interacting with God in an environment that isn’t mediated, or restricted, by us.

I hope that they continue to speak to God and that God talks back. I hope they know God for themselves and not just the God who is presented to them. I hope that one day, they will see the God who sees them. I hope this for myself too.

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of the women and girls in this community.