by Lilly West, 2023 Undergraduate Summer Research Fellow in Lived Theology

“By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.” (John 13:35)

Jesus’s words echo through Mt. Zion’s sanctuary on the Reverend’s voice. A chorus of amen’s sound from the congregation. Another minister stands at the pulpit and breaks into song.

“Resting on my feet,” as Reverend Edwards calls it, in the sanctuary of Mt. Zion, I am surrounded by laughter and expressions of joy, shouts of praise from the congregants around the room. The expression of unified community creates an atmosphere of self-forgetfulness to the end that, enlivened by cheery smiles and worship, standing becomes restful.

I return home, sit on the couch, and lean into James Cone and Malcolm X. Once again, a certain self-forgetfulness takes over. Cries for liberation and shouts of pain and suffering ring out. This unified community bands together in strength through the concrete and eschatological promise of Jesus as the “eternal event of Liberation in the divine person who makes freedom a constituent of human existence.”[1]

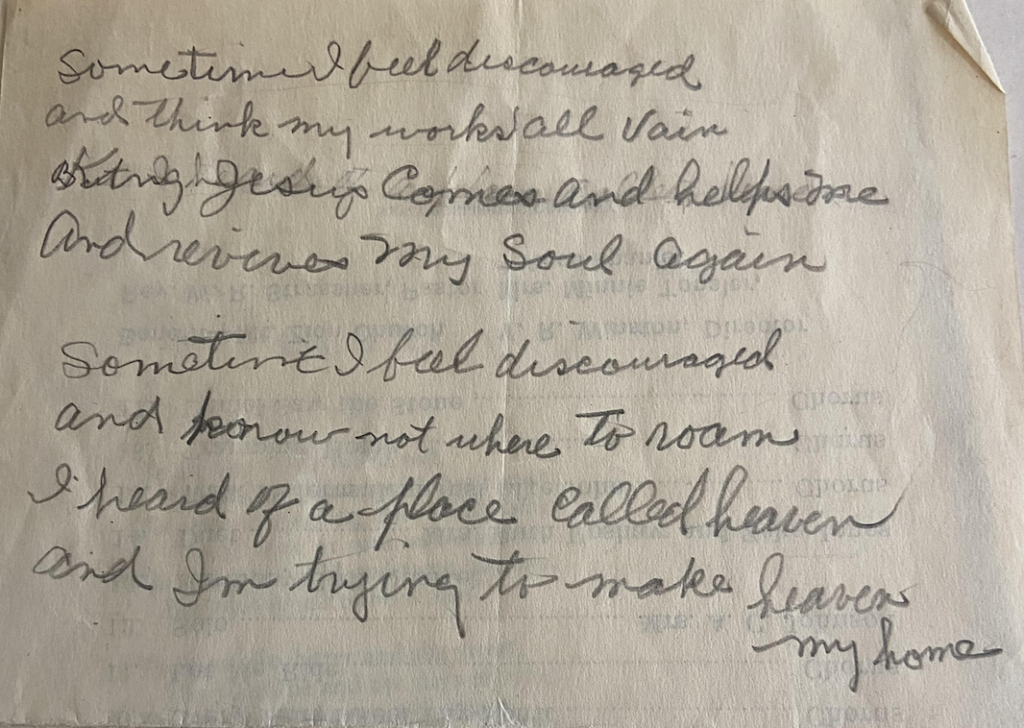

This community scribbles in smudged pencil on the back of a 1935 Mt. Zion choral program the words:

“Sometimes I feel discouraged,

And think my works all vain,

But Jesus comes and helps me,

And revives my soul again.

Sometime[s] I feel discouraged,

And know not where to roam,

I heard of a place called heaven,

And I’m trying to make heaven my home.[2]

These past few weeks invited me to dwell on that last line, “trying to make heaven my home.” In one sense, I hear a reminder that Christ followers are called to live with a constant awareness of our promised reality of eternal liberation. But, I fear stopping there dilutes this ethic of liberation. That awareness surely bids us to live into that reality, to resist every system of oppression and exploitation, every lived experience of sin. I am not sure what form this resistance takes, but I have confidence it is not an “ethic of the status quo”[3] which condones the brokenness of our world. Our God of the oppressed is a liberator. His good creation will be fully redeemed. I think, or at least I hope, we, as Christ’s body, get to participate in the process of liberation in the murky state of “already” and “not yet.” Jesus “inaugurat[ed] [the] liberation of our social existence, creating new levels of human relationship in society.” As his body, do we not also liberate?

However, in another sense, I hear that liberating truth and am not sure what to do with it. The realities and histories of oppression and exploitation are not accessible to me in the same way that they are for Cone, Malcolm X, and the author of the note on Mt. Zion’s choral program. I am not even sure it would be appropriate for me to apply Cone in the context of Mt. Zion’s liberated, self-forgetful joy. As the pastoral team at Church of the Good Shepherd models, the Christian position is to be deferential to a story that precedes us.

Cone writes that all he can do is “bear witness to [his] story, to tell it and live it, as the story grips [his] life and pulls [him] out of nothingness into being.”[4] Listening in loving humility “invite[s] [us] to move out of the subjectivity of [Our] Own Story into another realm of thinking and acting.”[5] Our witness and our fight, by which the world will know us, must be humble, liberating love.[6]

[1] Cone, James H. God of the Oppressed. 34-35

[2] Adaptation of Hide Thou Me

[3] Cone, James H. God of the Oppressed. 199

[4] Cone, James H. God of the Oppressed. 102-103

[5] Cone, James H. God of the Oppressed. 102-103

[6] Perkins, John. Welcoming Justice. 128

Learn more about the Lilly’s Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship in Lived Theology here.

The Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia is a research initiative, whose mission is to study the social consequences of theological ideas for the sake of a more just and compassionate world.