Part of my work with the Project on Lived Theology, includes meeting with my mentor Jonathan on a weekly basis to discuss the readings that we have been going through together. For the past two weeks we have been reading the “biography” of a Civil Rights group, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), called Many Minds, One Heart. My past few blogs have seen the recurrence of a few key actors in the movement, most notably Ella Baker, who have not only challenged my perception of the Civil Rights Movement by changing the focus to ordinary individuals but have also challenged me on a personal level, specifically with how I relate to people. At the heart of this movement was a desire to build relationships founded on listening, and only through that attentive practice could one successfully discern the actions to take in a given community.

The driving force behind Miss Ella Baker’s tactics was its relational nature. By listening to people, one can better understand their wants, needs, and desires, and then act accordingly. Ann Atwater, the woman largely responsible for integrating Durham Public Schools, performed this practice this by asking people “What do you want?” She said that this was the key to developing communities. After asking what someone wants, she would teach, we must work with them toward that goal until we’re halfway there, and then tell them what we want. This process is one of involvement, one of achieving goals by creating relationships with true “wants” at their heart.

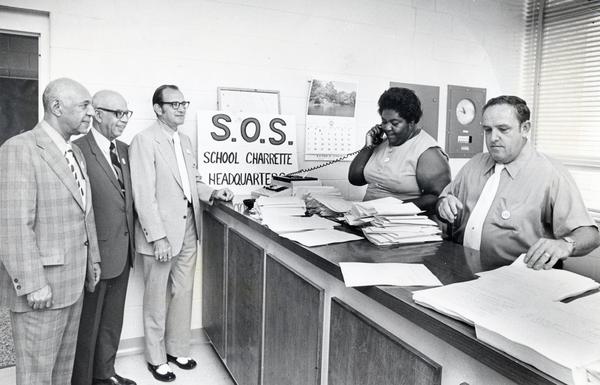

This process is what helped Ann Atwater work with C.P. Ellis, an American segregationist and Exalted Cyclops of the Durham Ku Klux Klan, to successfully integrate Durham Schools. After discussing what they wanted and listening to each other, this militant black activist and militant white segregationist realized that they both desired the best schooling for their children and that in order to accomplish this Durham schools had to be integrated. At the end of the ten-day integration session, C.P. Ellis stood in the front of the room. He held up his Klan membership card and said to everyone there, “If schools are going to be better by me tearing up this card, I shall do so.” And so he did. Ellis renounced the Klan that night and never returned. Other Klansmen threatened his life and never talked to him again for the next 30 years.Thus began integration, and more specifically, a genuine, lasting friendship between the two unlikeliest people in Durham, all through listening to the wants of others.

Last Friday Jonathan challenged me to do just this at Urban Hope. There is the distinct possibility, he noted, that I could go all through Urban Hope and have an intensely positive experience, one filled with personal reflection, realizations, and growth. I could live life with these kids throughout this entire summer and let it inform and influence the actions that I take when I return to the Charlottesville community. Perhaps even more than that, my experience at Urban Hope could profoundly shape the rest of my life, causing me to branch out beyond what I had previously intended and create a more intense involvement with urban youth, wherever I may end up. All of these things are great, he said, and would indicate a very rewarding summer experience. But suspended in the air between his sentences I felt the implication of all those scenarios: none of those mean much to the kids at Urban Hope beyond this summer.

The question Jonathan wanted me to ask myself was this: what would it look like to treat these kids as Miss Baker treated folks, or how Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis treated each other? How could I find out what these kids want and embark on a journey of fulfilling that desire in their lives? What is it that I can do now, here in Durham, to build up the Walltown community by translating the desires of its youth into concrete action?

“What do you want?” is a difficult question for any adult to answer truthfully, so how much more challenging would it be for a child if asked? Jonathan encouraged me to find alternative ways of posing this question, of searching out its answer in the lives of my campers. What makes them happy? What makes them angry? To which “wants” do their everyday actions point?

I have only been thinking about these questions for a couple days but a few answers immediately came to my attention. Most obvious to me was that the actions of these kids point to what seems like a deep desire for affirmation, to be told that they matter. Perhaps every child feels this way, and I’m sure to some degree they do, but this desire seems so real here in Walltown. I don’t want to generalize the lives and realities of the folks in this community but I am sure that at least some of these kids come from incredibly difficult families where they compete with so many things for the loving attention of their parent(s), grandmother, or foster parent.

I’ve tried to put myself in their parent’s shoes. I imagine a life, for example, in which I was financially unable to receive a college education and now work multiple jobs to provide for my children. In this life I face daily the realities of a difficult neighborhood and must somehow deal with the stresses and burdens that come with it. My financial situation precludes many amenities that make life easier for me and my family, like health care, legal services, or good education. And on top of all these things I must also provide love and attention to my kids… It seems difficult to accomplish theoretically, and I’ve seen with my own eyes that it is difficult to accomplish for many in Walltown. When questions of survival are on the table, “quality” time with children may seem an unaffordable luxury.

Where, then, do I come in? If what these kids want is to be affirmed, to be shown that they do in fact matter, then this is something that I, as someone who interacts with them daily, can do. One theme throughout camp that we’ve been revisiting with the kids is that as Christians we can understand our beautiful identity as children of God, made in His image. Addressing their wants, however, requires me to see that truth as well, and to love them accordingly. While seemingly simple, I am beginning to understand that this is a part of my time here that I cannot ignore or push to the side; it must be at the forefront of every interaction that I have with the campers. My role extends past a camp counselor merely here to maintain the peace and begins to break into the realm of mentor and friend, a role that can better contribute to the Walltown community. In this role I hope to discover more and more “wants” of Walltown and to continue working with Urban Hope to see them addressed.