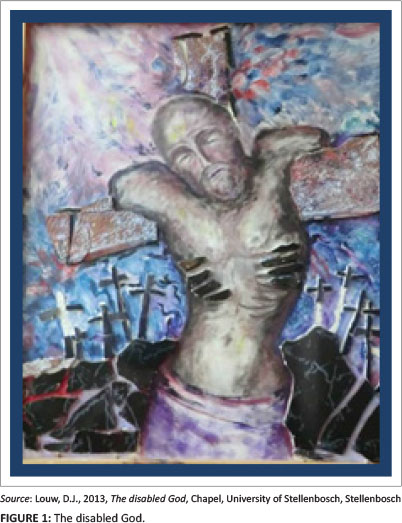

“The disabled God embodies practical interdependence, not simply willing to be interrelated from a position of power, but depending on it from a position of need.” –Dr. Nancy L. Eiesland

Although I’ve technically been working at the Virginia Institute of Autism (VIA) for over a month now, it wasn’t until last week that I think I was officially inaugurated. I was sitting at the kids’ kitchen table helping a student with his breakfast when I heard a rush of steps behind me. Thump thump thump… “OUCH!” I was nearly dragged out of my seat by one of our newer students, David,* who decided to grab a handful of my hair on his way to the playground. Before I realized what was going on, his instructor snatched away his hand and led him to the door, apologizing profusely. It was nothing serious (although I do remember looking much more to the left than usual that day), and I learned that incidents like that have happened to most of the instructors in my classroom. Later that day during recess, a fellow instructor called to me, “Glad to hear you’re officially one of us!”

At the end of that week, I met up with my supervisor for a routine check-in to make sure everything was going well. We ended up discussing some of David’s behavior as she pulled up a chart cataloguing his misbehaviors this past month. As I asked questions about his development and previous schooling experience, I noticed how difficult it was to keep from invoking the concept of “normalcy” into the conversation. David does not fit in well to existing paradigms. While it is true to say that he should probably learn to stop pulling people’s hair, referring to all of his behavior as “problem behavior” can sometimes cause us to forget the complex nature of his personhood. It is much easier to view someone in terms of how they relate to one standard or another rather than to define them on their own terms. It’s a problem Dr. Nancy Eiesland describes well in her book The Disabled God as a woman with disabilities herself.

I have to admit, I was a bit apprehensive about this week’s book at first, due to its label as a work of liberation theology. As someone who tends to highly value a rational approach to questions of faith, I’d heard less-than-favorable evaluations of liberation theology as “highly emotional” and “subjective” in the past. Dr. Jones, my theological mentor for this internship, explained to me that, indeed, there are some who conceive of liberation theology as simply “ideology hacking Christian thought” rather than legitimate theological reflection. He did so while gesturing toward the bookshelves above his desk, which held all the sorts of theology I never knew existed: black theology, feminist theology, queer theology, Latin-American liberation theology, and more.

I’m realizing more and more how little I know of theology. In reality, I’d only had experience with systematic theology—which attempts to answer theological questions in an abstract, purely rational, and therefore objective, systematized way. Liberation theology came along and said “NOT SO FAST, BUCKO,” making the point that theology has always been bound to context because knowledge is always mediated through a subject–the person. This is true of all thought—even systematic theology. Although it prides itself on its objectivity, systematic theology is often bound to the context and experience of highly educated, white men. But don’t call Francis Schaeffer on me just yet. Realizing that all knowledge is mediated through a subject does not necessarily make the knowledge itself subjective in the sense that there is no universal truth. It does call our attention back to the mediator and clue us in to what the person’s context tells us about the knowledge itself.

As you can imagine, this makes theology pretty messy (as if Christian theology weren’t messy enough already). There are lots of different people on this little blue-green planet, each with a unique story and outlook on life. The picture is one of chaos, no doubt. But I’m told that some of the best things in life are messy, especially genuine relationships like the ones instructors at VIA have with kids like David. The mess arguably makes theology a lot more interesting, accessible, and meaningful in everyday life.

This is exactly the aim of Dr. Nancy Eiesland in her work, The Disabled God. Through her experiences as a woman with disabilities, she strives to construct a more subject-centered paradigm for the theology of disability. Rather than merely being objects upon which people without disabilities do research, people with disabilities are given a voice. And more importantly, the Christian God is seen for what He truly is: a disabled God. Eiesland conceived of the Incarnation as God voluntarily disabling himself. At first glance, this does not appear to be terribly revolutionary thinking—Christian thought has recognized God’s taking on human limitations for millennia. However, framing the Incarnation as the taking on of a disability is the perfect example of theology which connects the mundane with the holy—for it connects Jesus’ experience as a human with the experiences of other limited humans. Not only does Jesus enter the world as a body, with all the quirks and particularities each body uniquely has, this body is beaten and broken. Even when he is resurrected, the scars are still on his hands and feet. Rather than being a sign of weakness, they are a sign of his true identity and a mark of his love. This blasts away conflations of disability with sin. The Incarnation is “a divine affirmation of the wholeness of nonconventional bodies” (Eiesland 87).

I realized that I’ve been playing into these notions of the “cult of normalcy” even in the way I describe this internship to people. The key line I always used was: “I’m reading and writing about how the Christian church can learn to better serve individuals with disabilities.” This sort of service language only widens the gap between “us normal people over here” and “those disabled people over there.” I no longer think that learning how to better serve people with disabilities is what the Church needs. This is arguably a dangerous attitude which can give us a messiah complex and turn disability into something to be treated rather than a person to be known. I believe what Christians need is nothing less than an entirely new way of thinking about and relating to people, including themselves. This requires a fundamental anthropological shift which privileges mutual vulnerability and interdependence as the new ‘norm.’ Time to cancel that subscription to the cult of normalcy, people. I don’t believe anything less will do.

I realized that I’ve been playing into these notions of the “cult of normalcy” even in the way I describe this internship to people. The key line I always used was: “I’m reading and writing about how the Christian church can learn to better serve individuals with disabilities.” This sort of service language only widens the gap between “us normal people over here” and “those disabled people over there.” I no longer think that learning how to better serve people with disabilities is what the Church needs. This is arguably a dangerous attitude which can give us a messiah complex and turn disability into something to be treated rather than a person to be known. I believe what Christians need is nothing less than an entirely new way of thinking about and relating to people, including themselves. This requires a fundamental anthropological shift which privileges mutual vulnerability and interdependence as the new ‘norm.’ Time to cancel that subscription to the cult of normalcy, people. I don’t believe anything less will do.

*Names of the students have been changed to protect privacy.

Eiesland, Nancy. The Disabled God: Toward a Libertory Theology of Disability. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. Print.