There is only one thing that I dread: not to be worthy of my sufferings. – Dostoyevsky

Viktor Frankl (26 March 1905 – 2 September 1997) was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist as well as a Holocaust survivor. On the night he thought was his last, Frankl turned to his friend Otto and said,

Listen, Otto, if I don’t get back home to my wife, and if you should see her again, then tell her that I told of her daily, hourly. You remember. Secondly, I have loved her more than anyone. Thirdly, the short time I have been married to her outweighs everything, even all we have gone through here.

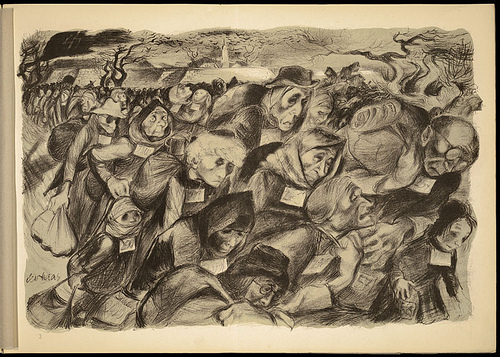

Viktor Frankl with his wife, Tilly, before they were transported to Auschwitz in 1944. Tilly did not survive the year.

Frankl believed that “love is the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire” (Frankl 38). But what allowed him to hold onto this believe so fervently amidst the moral deformity of the Holocaust? In Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl’s autobiographical testament of his time in Auschwitz, he offers this explanation: “Those who know how close the connection is between the state of mind of a man, his courage and hope, or lack of them and the state of immunity of his body will understand that sudden loss of hope and courage can have a deadly effect” (75). To illustrate his point Frankl details for us his theory on the record high death rate in Auschwitz during Christmas 1944 to New Years 1945: that prisoners died because they had expected to be home before Christmas. When they realized this was not to be they completely lost hope in life beyond the concentration camp.

Last week, when reflecting on community engagement, I discussed how the sacrament of the present moment allows us to be stronger community members by enhancing our awareness of our connectedness to others. However, in his psychoanalysis of Holocaust prisoners, Frankl offers a different perspective: “It is a peculiarity of man that he can only live by looking to the future…And this is his salvation in the most difficult moments of his existence, although he sometimes has to force his mind to the task” (73).

The Catholic Church proclaims that human life is sacred and that the dignity of the human person is the foundation of a moral vision for society. As far as threats to human dignity go, the Church includes abortion, euthanasia, cloning, the death penalty and war. I feel that it might be necessary to also add time poverty.

Time poverty, according to Maria Konnikova, is “what happens when we find ourselves working against the clock to finish something.” For someone who is financially comfortable, poverty of time is merely an unpleasant inconvenience. For someone whom lack of time is just one of their many burdens, time poverty becomes much more serious. Especially when you take into account that time poverty tends to bring about what Konnikova calls bandwidth poverty or, “the type of attention shortage that is fed by [financial poverty and time poverty].” She offers us the following example:

If I’m focused on the immediate deadline, I don’t have the cognitive resources to spend on mundane tasks or later deadlines. If I’m short on money, I can’t stop thinking about today’s expenses — never mind those in the future. In both cases, I end up making decisions that leave me worse off because I lack the ability to focus properly on anything other than what’s staring me in the face right now, at this exact moment.

And so we begin to see how our need to look to the future for hope and our need to be present in the moment for peace come into conflict. It is clear that we need space in our lives to develop healthy relationships with both “now” and “later” and that a lack of space to do so is detrimental to our overall well being. That poverty, in whatever sense we are discussing it, is not a static issue.

In the past week, my research team has visited Tiyani twice to conduct focus groups with nurses and community health workers (CHWs) from the surrounding area. Though I am not directly a part of the CHW study, my project partners and I got to help our other teammates out with implementing their focus groups. At the beginning of each session, we would go around the circle and ask each woman their name and how long they had been working. Most them had been CHWs for at least five years, some as many as fifteen. It was not until later in the day that I found out that none of these women are paid for rounds they do in their communities each week. They just do it because they believe it’s important.

The Catholic church teaches that our human dignity comes from the fact that we are all made in the image and likeness of God. Or, in the words of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, dignity is the idea that:

We are made for goodness. We are made for love. We are made for friendliness. We are made for togetherness. We are made for all of the beautiful things that you and I know. We are made to tell the world that there are no outsiders. All are welcome: black, white, red, yellow, rich, poor, educated, not educated, male, female, gay, straight, all, all, all. We all belong to this family, this human family, God’s family.

Maria Konnikova’s research on time poverty seems to make it pretty clear that having a deficit of time in one’s life makes it very hard to cultivate a sense of dignity or to honor that of others. However, throughout Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl insists that “he who has a why can bear almost any how” (Nietzsche).

The experience of camp life shows that man does have a choice of action. There were enough examples, often of a heroic nature, which proved that apathy could be overcome, irritability suppressed. Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions as psychic and physical stress…everything can be taken from man but one thing: the last of human freedoms–to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way (Frankl 65-66)

How can one begin to argue with such unfettered faith? Frankl offers us a no-holds-barred answer to the question of how to find dignity in suffering. Or (much) more simply, how to rationalize giving time to that which we might not logically have time for.

However, though I am deeply moved by Frankl’s words, I must return to the “almost” in the Nietzsche quote of which he is so fond. He who has a why can bear almost any how. Though I am humbled beyond belief by the grittiness of Frankl’s faith, I fear the depth of responsibility that he takes for his own well-being can almost makes us forget the severity of his aggressors’ actions. Ultimately, I still believe that the choices that we make are determined by the choices that we have. That spiritual freedom is only a possibility for those who have a concept of the spirit. That even though people like the community health workers that we met in Tiyani this week will always give me hope that people will do good and be good whether or not they have the time to do it, it is our responsibility to not make that choice a burdensome one when we can.

All that being said, sometimes the most we can do is assume the best of people. In this heartening TED Talk. Victor Frankl makes his case for why we should believe in others by offering us Goethe and a Flight Lesson:

If you are starting, here, wish to get here, say east, and you have a crosswind you will land here, so we have to do what we pilots call, eh ‘crabbing’ he told me, C-R-A-B. You have to head north of that airfield, and you have to fly that way, see? As if you’re headed in this direction. If you are heading here, above this airfield, you will actually land here. But if you head here [airfield] you will actually land here [below airfield]. This holds also for man I would say! If you take man as he really is you make him worse, but if we over estimate him–if we seem to be idealists–are overestimating and overrating man, and looking at him that high, here, above, you promote him to what he really can be.

Claire Constance is blogging from Limpopo, South Africa, this summer for the Summer Internship on Lived Theology. Learn more about Claire and the internship program here, and read more internship blog posts here.