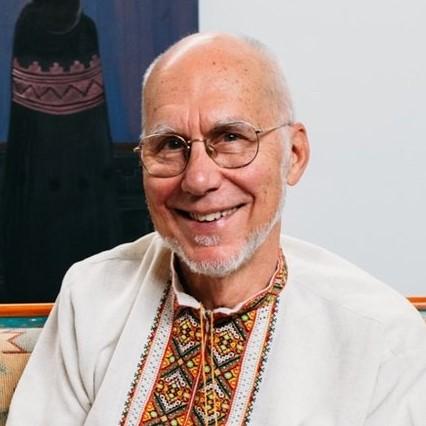

In his virtual presentation on December 2, 2025, Professor Larry Rasmussen reflected on the emotional and ethical challenges of climate crisis and ecological distress, weaving together personal stories, theological insight, and social-ethical analysis. He began with an anecdote about his young grandson’s early awareness of mortality, illustrating how existential dread emerges naturally yet does not define us, and that humans move between fear and resilience. Rasmussen then recalled theologian Dorothee Soelle’s reminder that many people “don’t have the luxury of despair,” noting that while some communities struggle simply to survive, students and scholars have the privilege, and responsibility, to reflect on climate anxiety and moral change.

Central to Rasmussen’s message was the theme of community, which he described as the grounding force throughout his career and a key remedy for ecological dread. Drawing from his experience in the Community of Christ in Washington, D.C., he emphasized that belonging and shared life give people the strength to face uncertainty.

He then outlined five essential elements for responding to climate anxiety in the Anthropocene:

- Warning and Survival: climate scientists as modern prophets calling attention to ecological crisis.

- Alternative Visions: imagining new ways of living beyond destructive patterns.

- Embodiment – turning visions into concrete practices and sustainable habits.

- Structural Change: recognizing that laws and institutions must reinforce just behavior, often preceding attitude change.

- Friendship and Celebration: sustaining hope and moral courage through joy and connection

Rasmussen concluded by distinguishing between “Holocene generations,” who grew up with climate stability, and today’s “Anthropocene children,” who inherit a more volatile world. Addressing ecological anxiety, he argued, requires not just knowledge but community, imagination, and collective action.

The Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia is a research initiative, whose mission is to study the social consequences of theological ideas for the sake of a more just and compassionate world.