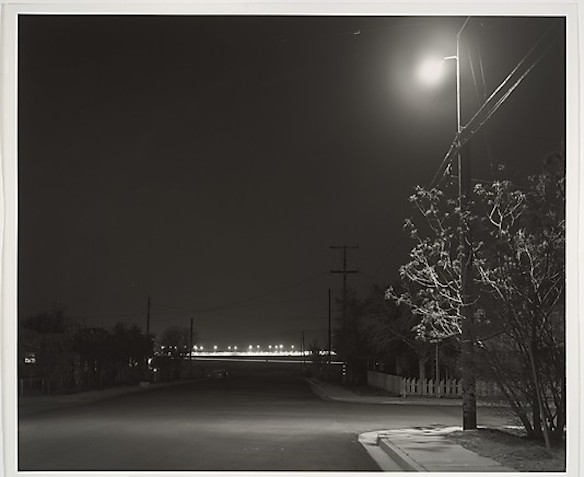

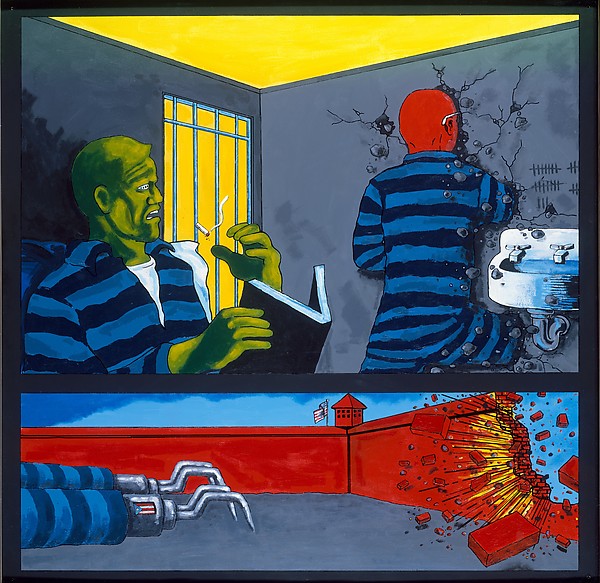

There is not a single inmate who should be trusted. We should stop using the word trustee in the prison. Not one of them is trustworthy, not even a trustee. In my notes from our ACRJ orientation, I’ve written this line. It can be attributed to some lieutenant at some prison in some cold city in upstate New York. Unfortunately, though, that opinion reaches far beyond that singular sentinel, frozen to the bars of some freezing New York prison. The whole prison system is built within a vacuum of trust—every crosswire window, blinking camera and slick tile floor. The house has long been prepared for attack.

There is not a single inmate who should be trusted. We should stop using the word trustee in the prison. Not one of them is trustworthy, not even a trustee. In my notes from our ACRJ orientation, I’ve written this line. It can be attributed to some lieutenant at some prison in some cold city in upstate New York. Unfortunately, though, that opinion reaches far beyond that singular sentinel, frozen to the bars of some freezing New York prison. The whole prison system is built within a vacuum of trust—every crosswire window, blinking camera and slick tile floor. The house has long been prepared for attack.

Of course, an environment perfectly devoid of trust is a feat too great even for the American penal system. No one can actually create a jail that exhausts all precautionary measures. Outfit the guard with bigger guns. Strip the visitors down to nothing. Force every inmate into solitary confinement. Threaten, like the God of Luther’s dark imagination, every misstep with death.

Once, spending the night at a friend’s house in high school, we decided to watch one of those documentaries on Netflix that no one ever watches. So we furiously scrolled backwards, like Cameron Frye’s dad’s car, into the forgotten annals and found a National Geographic film called Russia’s Toughest Prisons. In the most masochistic sleepover ever conceived, we watched the whole movie. All 44 minutes.

In case you were wondering, Russian prisons are nothing like Tina Fey’s portrayal in the latest Muppets’ movie. The documentary begins with a look at a prison known as Black Dolphin on the boarder with Kazakhstan. There, every guard wields an automatic rifle and every inmate is transported in the same position: hands bound behind the back, bent over at a forty-five degree angle, followed by a snarling German shepherd. They respond to every command with yes, sir. Every cell has a video camera. There are light and motion detectors. Every fifteen minutes a guard goes through the cells. They are not allowed to sit on their beds for sixteen hour stretches. Inmates share cells of fifty square feet in which they eat. And each cell is itself within a cell, behind three sets of steal doors. “All prison operations maintain the highest level of isolation.” (39:42)

ACRJ sports nothing close to this level of security. Inmates walk, unchained, escorted by guards—most of them less physically fit than their charges. Nathan and I walk unescorted in the facility, sealed with a badge: no escort required. My oxford button down and jeans, though, get me access into the break room, where the food accounts for the physical disparity between staff and inmate.

I recently was in a seminar discussing Kierkegaard’s Works of Love. In it, he gives a puzzling little reflection on love for the dead as the purest form of love. “When one wants to make sure that love is completely unselfish, one can of course remove every possibility of repayment. But this is exactly what is removed in the relationship to one who is dead. If love still abides, then it is truly unselfish”(349). Love he says is purest where there is no possibility of reciprocation, where the fault line between life and death becomes the one-way mirror across which we reach out to the Other.

One of the other students, particularly unsettled by the idea, began to talk about his brother-in-law in prison. He saw a striking similarity between the state of the dead, as Kierkegaard would have it, and the relational possibilities of an inmate, namely the inability to reciprocate. I do not recall the point he actually made. But I do recall getting excited…because we were talking about my thing now. “I actually taught in a jail this summer…” I do not recall the point I actually made. I do recall people looking at me with their eyes: he just wanted to talk about his thing now. I’ve since thought about the other student’s comparison—the jail to the dead. I am not entirely sure what I think about the love bit, or the purest form of love. But these three remain: trust, isolation and love.

Jürgen Moltmann in The Crucified God writes, “It is true that in a technocratic society all human relationships are reduced to the level of things, and general apathy is spreading on an academic scale. It is true that in a world of high consumption, where anything and everything is possible, nothing is so humanizing as love, and a conscious interest in the life of others, particularly the life of the oppressed. For love leaves us open to wounding and disappointment. It makes us ready to suffer. It leads us out of isolation into a fellowship with others, with people different from ourselves, and this fellowship is always associated with suffering”(62-63).

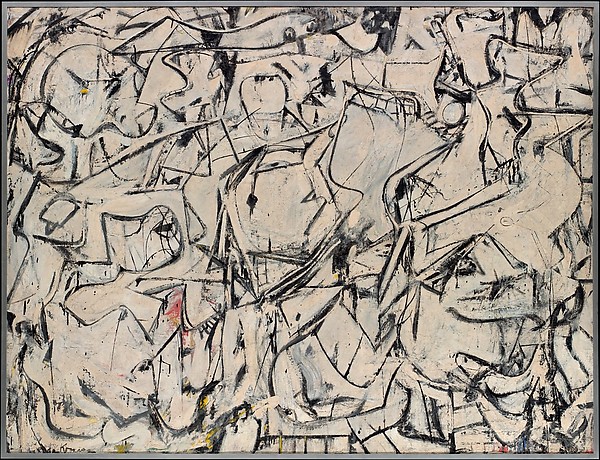

I hope it comes through here, as it did to me only upon rereading this paragraph, that the basic relationships between trust, love, and fellowship come through here. Love demands fellowship. Love demands that people come together in trust. Love demands the environment in which it thrives. Love draws us out of isolation, because it requires fellowship, and it opens us up to wounding, overcoming mistrust. We cannot remain alone—either in isolation or in self-concern. If we do so, we fight against love.

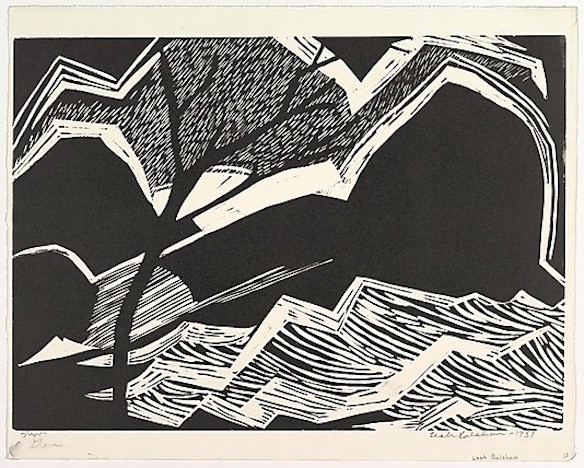

The jail fights against love. The jail is cold. It pours mean into their separate cells and binds them there like water in an ice tray. It sets them to the back of the societal icebox until they freeze alone. Love then comes like a flame. We cannot be kept apart, even when we forget our ID. A force among us begins to draw us together across the thin cracks in the wall.

I believe, then, that the task of the Christian in the jail is to learn to love the mistrusted in an environment of mistrust. Whatever this means, its does not mean that we take a system of mistrust as given. We go like a burning man into a fortress, a bush aflame in the desert. Perhaps though, simply being there is the first step.

Peter Hartwig is blogging this summer for the Summer Internship on Lived Theology. Learn more about Peter and the internship program here, and read more internship blog posts here.

Image information:

Miss Vesta is the education director at ACRJ. She’s a godsend.

Miss Vesta is the education director at ACRJ. She’s a godsend.