A new school year is upon us! Allow us to (re)introduce ourselves.

The Project on Lived Theology is a research community housed in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia. Our mission is to understand the social consequences of theological commitments, to foster collaborative research between religion scholars and practitioners, and to discern the wisdom of faith lived in service to others.

What We Do

We have several main initiatives. The Spring Institute for Lived Theology is an annual institute for theologians, scholars, and practitioners focused on issues of faith and social practice. Past SILT themes include social hope, the built environment, the language of peace, Civil Rights leader John M. Perkins, migration and the borderlands, and the enterprise of lived theology itself. The most recent SILT, held at U.Va. in May, celebrated ten years of spring institutes and furthered a book project that will share the enterprise of lived theology with a broader audience.

We have several main initiatives. The Spring Institute for Lived Theology is an annual institute for theologians, scholars, and practitioners focused on issues of faith and social practice. Past SILT themes include social hope, the built environment, the language of peace, Civil Rights leader John M. Perkins, migration and the borderlands, and the enterprise of lived theology itself. The most recent SILT, held at U.Va. in May, celebrated ten years of spring institutes and furthered a book project that will share the enterprise of lived theology with a broader audience.

The Virginia Seminar in Lived Theology supports theologians, scholars, and practitioners in writing single-authored books on theology and lived experience. Seminar members receive research funding and meet yearly to engage in creative and fruitful exchange. One of the distinctive features of the Virginia Seminar is that it brings together scholars who have primarily written for an academic audience and those writers and scholars who have made their mark writing for more popular, general audiences. Virginia Seminar books aim to be intellectually sophisticated yet accessible to a broad audience.

The Virginia Seminar in Lived Theology supports theologians, scholars, and practitioners in writing single-authored books on theology and lived experience. Seminar members receive research funding and meet yearly to engage in creative and fruitful exchange. One of the distinctive features of the Virginia Seminar is that it brings together scholars who have primarily written for an academic audience and those writers and scholars who have made their mark writing for more popular, general audiences. Virginia Seminar books aim to be intellectually sophisticated yet accessible to a broad audience.

The Summer Internship in Lived Theology supports two or three U.Va. students annually in a summer immersion experience designed to foster reflection on service as a theological activity. Students design and propose internships with established service organizations, and selected interns are matched with a theological mentor with whom they craft a reading list for the summer. Interns blog in conversation with their site experiences, readings, and conversations with mentors, and in the fall, interns present their reflections on the experiences as a whole at an event on Grounds.

The Summer Internship in Lived Theology supports two or three U.Va. students annually in a summer immersion experience designed to foster reflection on service as a theological activity. Students design and propose internships with established service organizations, and selected interns are matched with a theological mentor with whom they craft a reading list for the summer. Interns blog in conversation with their site experiences, readings, and conversations with mentors, and in the fall, interns present their reflections on the experiences as a whole at an event on Grounds.

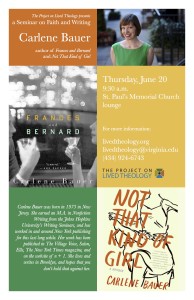

The Project on Lived Theology also hosts occasional lectures and seminars, which are publicized through our website, Facebook page, and mailing list as they are scheduled.

Our Resources

As a research community, the Project produces a wide range of resources. Several of our Spring Institutes have produced books, including Mobilizing for the Common Good: The Lived Theology of John M. Perkins and Religion and Politics in America’s Borderlands, both recently published. A book from the 2011 and 2013 SILTs is also underway. More book listings, as well as a collection of articles, audio files, videos, photos, and presentations can be found on our website.

As a research community, the Project produces a wide range of resources. Several of our Spring Institutes have produced books, including Mobilizing for the Common Good: The Lived Theology of John M. Perkins and Religion and Politics in America’s Borderlands, both recently published. A book from the 2011 and 2013 SILTs is also underway. More book listings, as well as a collection of articles, audio files, videos, photos, and presentations can be found on our website.

The Project also houses a physical and digital archive entitled, The Civil Rights Movement as Theological Drama. The archive is highly interactive and brings the theological drama of the American Civil Rights Movement to life. Through personal interviews and primary documentary evidence, much of which is previously unpublished, the archive tells the stories of the time period in light of the hypothesis that God was–in some perplexingly and hitherto undelineated way–present there. You can read more about it here, or visit it here.

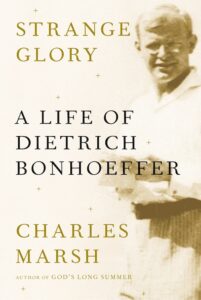

Project executive director, Charles Marsh, is teaching a course this fall entitled Kingdom of God in America. The course examines the influence of theological ideas on social movements in twentieth and twenty-first century America. Its primary historical focus is the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s and 60’s but will also explore the student movements of the late 1960’s and a variety of faith-based social movements of recent decades. Professor Marsh’s forthcoming book, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, is scheduled for release on April 22.

Project executive director, Charles Marsh, is teaching a course this fall entitled Kingdom of God in America. The course examines the influence of theological ideas on social movements in twentieth and twenty-first century America. Its primary historical focus is the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s and 60’s but will also explore the student movements of the late 1960’s and a variety of faith-based social movements of recent decades. Professor Marsh’s forthcoming book, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, is scheduled for release on April 22.

We invite you to connect with the Project through our website, Facebook page, and email list. And we encourage you to take advantage of our resources, especially the Civil Rights archive. Please email us with any questions, and best wishes for a great semester at U.Va.

On Wednesday, September 18, Dr. Marie Griffith will give a lecture entitled, “Christians, Sex, and Politics: An American History.” Dr. Griffith is a U.Va. alumna, director of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, and John C. Danforth Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Washington University in St. Louis.

On Wednesday, September 18, Dr. Marie Griffith will give a lecture entitled, “Christians, Sex, and Politics: An American History.” Dr. Griffith is a U.Va. alumna, director of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, and John C. Danforth Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Washington University in St. Louis.

We have several main initiatives. The

We have several main initiatives. The