The names in this post will be changed to protect students’ privacy.

There was no fog in London until Whistler started painting it. – Oscar Wilde

“Next up we have Claire Constance, from the University of Virginia. Claire, we hear that the thing you do best is spoken word poetry so we would like to invite you up on stage to battle one of our own students, and see who comes out on top.”

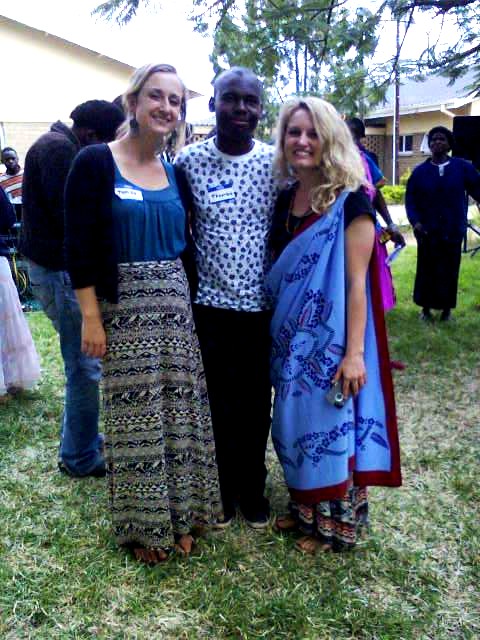

I gave Lufuno and Hulisani my you’ve got to be kidding me look. They both laughed, slapped me on the back and started shoving me towards the front stage.

It was a Wednesday afternoon and we were at the University of Venda weekly open mic. Hulisani had made a point to tell the students who ran the open mic that his friends from the US were going to come and participate, so they had planned the setlist so the acts alternated between U.Va. and UNIVEN students. And now it was my turn.

I’m not a very competitive person. I’m all for challenging myself and trying new things, but I’ve never been the person who was going to fight you for the last slice of pizza, let alone go head-to-head against you in front of a crowd to prove which of our poems was better.

I looked out at the sea of tables in the auditorium, then smiled weakly at my opponent.

“Dakalo, you’re first!” The MC roared, “show us what you’ve got!”

My opponent spoke like a dancer: his words were choreographed perfectly. Each line of his poem two-stepped into the other, and when he was all finished, it was clear the crowd was having such a good time they were just about ready to jump up on stage with him.

“Next up, Claire Constance from the University of Virginia!”

I was handed a microphone. I paused to look out at everyone and grinned.

“Hey, everyone, thanks so much for having us here today. Dakalo is going to be a tough act to follow but if you’ll hear me out, this poem is called ‘Rules’.”

As I began to recite my poem, I was overwhelmed with a deep feeling of gratitude. All summer I have felt foreign. I have felt how I would imagine a house plant must feel: both uprooted and walled-in at the same time. Not unhappy, because I still have more than I really need, but out of place all the same.

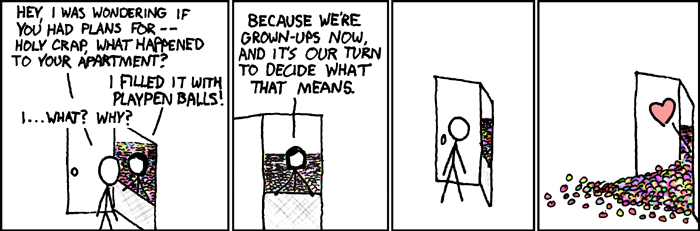

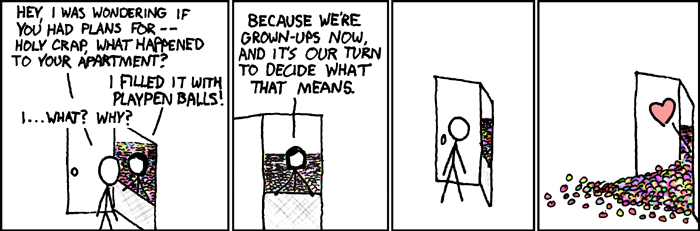

Finding that place where you belong, brought to you by XKCD comics.

But somehow at this open-mic, that all went away. Here was something that we all understood. What’s more, here was something that we all respected: an art that combines storytelling and musicality. For the the first time that summer, I felt like I was a part of the UNIVEN community; that instead of being their guest I was their friend.

* * *

This week I have been reading Art as Therapy by Alain de Botton and John Armstrong. The book, on the whole, tries to grapples with why art is important to us by offering a variety of different answers to the question, “What is the point of art?” My favorite section of the book begins by asking a compelling question:

Can we get better at love?

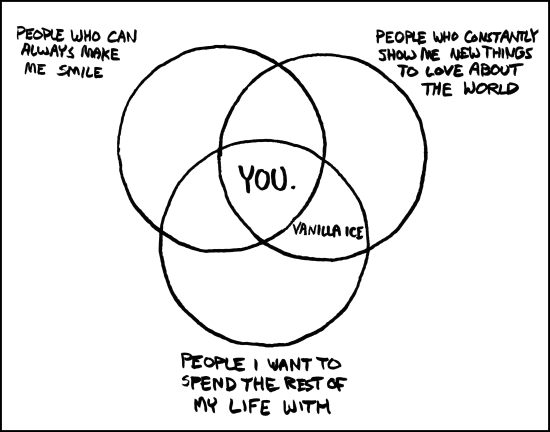

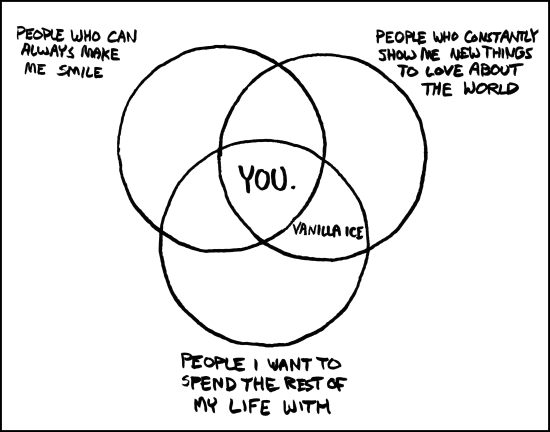

Romantic regrets, brought to you by XKCD comics.

For most of my life, I thought of love as something more or less a fixed quality. Love, being one of those universally important things, was good wherever and whenever it arrived. As something that we all both want and need, I saw it as a great equalizer, something which would be hard to edit and potentially impossible to revise, given that it was buried so deep in the archeology of our hearts.

But in the past few years I have begun to understand what Oscar Wilde’s Basil Hallward meant when he said to his friend Lord Henry Wotton “You like everyone; that is to say, you are indifferent to everyone.” Love, it seemed, was not above context but required context. To love everyone or everything was to misappropriate the emotion entirely.

The Bible has plenty of swell things to say about love. However one of my favorites is 1 John 4:8, “Whoever does not love, does not know God, because God is love.”

Armstrong and de Botton define art’s mission as “to teach us to be good lovers: lovers of river and lovers of skies, lovers of motorways and lovers of stones. And — very importantly — somewhere along the way, lovers of people” (103). They provide a response to this mission with another age-old question:

What is it like to be a good lover?

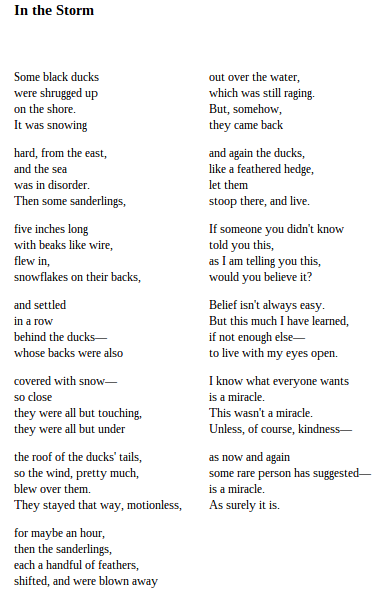

True vulnerability, brought to you by XKCD comics.

And the answer both to loving art and loving those who are most dear to us, they insist, is in a combination of attention to detail, patience, curiosity, resilience, sensuality, reason and perspective.

The Catholic Church teaches that “we show our respect for the Creator by our stewardship of creation.” In other words, we show our love for God at least in part by how we love people and the planet.

* * *

After I finished reciting my poem I came back to my table where Lufuno and Hulisani were still sitting. They both wrapped me in big hugs.

“Wow,” Hulisani said shaking his head, “That was was just…wow.”

I laughed, “What, Hulisani, you surprised that I write poetry?”

“No, I’m surprised you write poetry well.” I feigned horror.

“What’s that supposed to mean, Hulisani?” Lufuno jumped in.

“What he means is you write poetry like you’re from Venda!” Hulisani nodded his head in agreement. I beamed. Though I was still suspicious that the crowd had voted me the winner of the poetry battle as a gesture of respect to me as a visiting student, I couldn’t hide my delight.

This was the goal after all: for the art and the love to be one and the same.

Claire Constance is blogging from Limpopo, South Africa, this summer for the Summer Internship on Lived Theology. Learn more about Claire and the internship program here, and read more internship blog posts here.

Virginia Seminar member Susan R. Holman was recently interviewed by “The Poor in Spirit,” a theology blog written by Alvin Rapien. She discusses her influences and current literary interests, as well as her perspective on Christian responses and approaches to human poverty and suffering, a subject she has expanded upon in several of her books.

Virginia Seminar member Susan R. Holman was recently interviewed by “The Poor in Spirit,” a theology blog written by Alvin Rapien. She discusses her influences and current literary interests, as well as her perspective on Christian responses and approaches to human poverty and suffering, a subject she has expanded upon in several of her books.

On Wednesday, October 1, the Project on Lived Theology summer interns Claire Constance and Peter Hartwig will share their field reports, a composition of experiences gained through the PLT internship program.

On Wednesday, October 1, the Project on Lived Theology summer interns Claire Constance and Peter Hartwig will share their field reports, a composition of experiences gained through the PLT internship program.  On Wednesday, September 24, Paul M. Gaston, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Virginia, will lead a seminar on the Civil Rights Movement in Charlottesville, Virginia. The seminar will begin at 3:30 pm in the University of Virginia’s

On Wednesday, September 24, Paul M. Gaston, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Virginia, will lead a seminar on the Civil Rights Movement in Charlottesville, Virginia. The seminar will begin at 3:30 pm in the University of Virginia’s

On Wednesday, September 10, Project director Charles Marsh will speak on his biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer at

On Wednesday, September 10, Project director Charles Marsh will speak on his biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer at