“There is no safe investment. To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.” – C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves

Ours is a society which values the written word. And not without reason. Words are powerful—they have the ability to express emotion, unify people, even change a mind. What’s that old saying? “The pen is mightier than the sword”? Where would we be without works like Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Elie Wiesel’s Night (or the Bible, for that matter)? Words change us. But I fear that sometimes the elevation of the written word comes at the expense of the devaluing of other forms of communication. When you picture the idea of “communication,” you’re most likely to imagine words in one form or another. Nonverbal communication, such as body language or augmentative communication devices (like the ones used by the students at the Virginia Institute of Autism) may not be the first things that pop into your mind.

Certainly, this is no grievous sin, but it does highlight what I think is a discernibly negative consequence of the written word’s supremacy. It has to do with vulnerability. This is a theme I feel resurfaces in every book I’ve read for this internship. All communication, written and otherwise, necessarily entails varying degrees of vulnerability. When you communicate with another, you open yourself up to the possibility of being misunderstood; there is never (ever) a foolproof method for ensuring another’s complete comprehension. Interestingly, it seems to me that we assume the written word is “invincible.” We consider it the most professional and efficient means of communication. The success of an academic’s career, for example, depends in large part on the success of her written publications. But even the written word is far from universally communicable. Disregarding the fact of the many different languages in the world, the written word certainly doesn’t mean much to the 774 million people in the world unable to read.

I wonder: is there any form of communication that is truly universal? I think Taylor* has given me the answer to this question. Yesterday I sat working with him at his desk at VIA just as he had earned a break. Because Taylor is nonverbal, and uses an app on his school iPad to communicate, the words he is able to say are limited to what VIA instructors have made available on the iPad for him to say. He chooses pictured icons corresponding to words, and in this way is able to communicate his wants and needs to us through basic sentences like “I need bathroom” or “I want Little Einstein’s.” Yesterday it was “I want blue swing.” VIA has a wonderful playground behind its classroom buildings, and there is a certain blue swing Taylor loves. So we started making our way outside. Before I knew it, he began to act out. Veering off to the school’s track, away from the playground, Taylor was making sounds which suggested he did not in fact want to be anywhere near the blue swing.

In these situations, instructors are encouraged to prompt the child, “Hey, I don’t understand. If you want to tell me something, you can use your voice!” with the “voice” referring to the child’s iPad. Again he repeated, “I want blue swing.” Alright, I thought, hoping against a repeat of the previous hair-pulling incident. I guess we’ll give this one more try. Still appearing noncompliant, Taylor nevertheless made it to the blue swing. Unfortunately, things did not get better from there. Quite the tantrum commenced; crying, screaming, throwing—the whole shebang. Yikes.

Thankfully, the school’s occupational therapist was also out on the playground. Shooting me a sympathetic glance, she came over and tried to gain control of the situation. When Taylor’s tantrum only escalated, she pulled out a walkie-talkie and murmured something that sounded like spoken Morse code. While I was still trying to figure out what in the world she said, and if she was secretly in the CIA, I saw two instructors from my classroom literally sprinting out to the playground. This really is some sort of secret spy operation, I gaped.

The odds shifted when they arrived: it was four to one, and much easier to control Taylor’s behavior. As we were finally walking back, I expressed my confusion over the situation to Laura, heroic sprinter #1. “I don’t get it—he kept saying he wanted the blue swing, but he clearly didn’t actually want it.”

She thought for a moment and replied, “What may have happened is that he wanted to walk around the track, but didn’t know how to ask for it. It’s a new icon we’ve added, and he doesn’t really know how to find it yet. We probably should have guided him to that icon on his iPad so he could ask for it.”

Oops. “We” definitely means me. Although I sensed no animosity in Laura’s response to me, it did make me realize my true error in that situation. Taylor clearly did not want to be on the swing. But, as a member of this society which prizes verbal communication above all else, I assumed that Taylor’s words were more meaningful than his nonverbal communication and directed him toward the swing and away from the track. His body-language communicated a different message than the words he spoke through his iPad. The lesson I learned was this: especially for people who tend to use alternative forms of communication, we need to be good listeners. Listening is irreplaceably important. And oftentimes it is just when we think we are doing a fine job of listening that we are in fact utterly failing. For the other person, the experience of being misunderstood is aggravating at best and painfully wounding at worst. The consequences are often so much more than a temper tantrum on the playground.

But listening is also often very hard. This week I’ve been reading Places of Redemption by Mary McClintock Fulkerson, who writes an ethnography of Good Samaritan Church in Durham, North Carolina. Recognized as a significantly racially diverse church (a status applicable to less than 10% of churches), Good Samaritan also has many members with disabilities. Their outreach is shaped by the drive to reach out to people ‘not like them,’ largely out of the story of the Ethiopian eunuch as described in Acts. As Fulkerson writes, “The eunuch became a symbol to them for those ‘people who are different from us, people who usually are looked over and passed over, that regular established church folks would pass on the street’ and never think of in relation to their church.” The way this community defines faith—as a networked transformative project rather than merely a set of beliefs or moral laws—is central to the way they have incorporated so many different people into their fellowship.

All of this fits together. Listening is hard because it means conceding the control we crave in relationships. It is all too easy to interpret someone as saying what you want them to say rather than what they are actually saying. To truly listen is an act of will which tells the other, “You are free to be who you truly are, and I will accept that.” This takes courage and an openness to being wrong which overshadows our death-grip on control.

I think what Taylor taught me yesterday was that it’s sometimes the less obvious forms of communication which speak clearer than the traditional written word. Nonverbal communication often requires more vulnerability precisely because it requires us to be better listeners. Faith, like other relationships, is potentially life-changing because it is necessarily dynamic. It’s only through good listening and open vulnerability that we can begin to let God transform us and our communities to what we were created to be.

*Names of students and instructors have been changed to protect privacy.

Fulkerson, Mary McClintock. Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldy Church. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. Print.

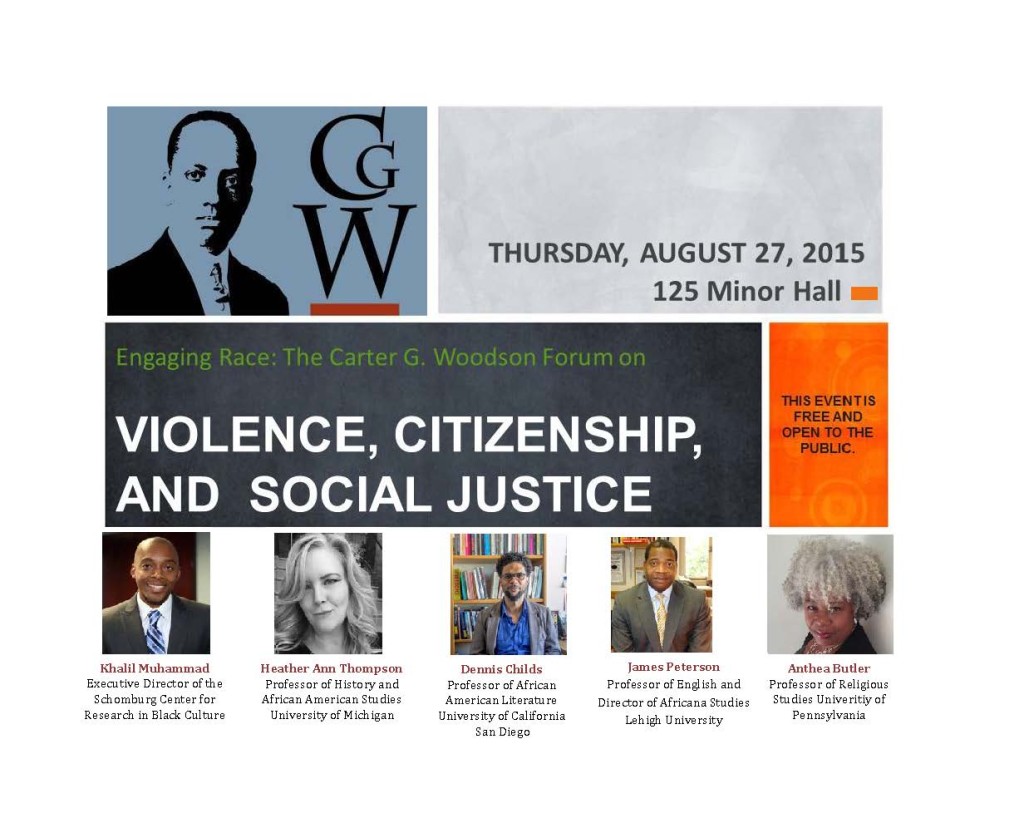

Next week, the Carter G. Woodson Institute will host a forum titled “Engaging Race: Violence, Citizenship, and Social Justice.” Anchored by Khalil Muhammad, Executive Director of the Schomburg Center in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, this forum is inspired by recent events in Charleston, South Carolina. This event is co-sponsored by the Project on Lived Theology, will be held on Thursday August 27 at 4:30 at the University of Virginia in 125 Minor Hall.

Next week, the Carter G. Woodson Institute will host a forum titled “Engaging Race: Violence, Citizenship, and Social Justice.” Anchored by Khalil Muhammad, Executive Director of the Schomburg Center in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, this forum is inspired by recent events in Charleston, South Carolina. This event is co-sponsored by the Project on Lived Theology, will be held on Thursday August 27 at 4:30 at the University of Virginia in 125 Minor Hall.

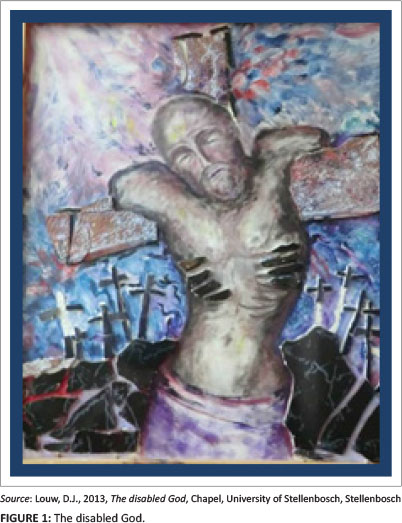

I realized that I’ve been playing into these notions of the “cult of normalcy” even in the way I describe this internship to people. The key line I always used was: “I’m reading and writing about how the Christian church can learn to better serve individuals with disabilities.” This sort of service language only widens the gap between “us normal people over here” and “those disabled people over there.” I no longer think that learning how to better serve people with disabilities is what the Church needs. This is arguably a dangerous attitude which can give us a messiah complex and turn disability into something to be treated rather than a person to be known. I believe what Christians need is nothing less than an entirely new way of thinking about and relating to people, including themselves. This requires a fundamental anthropological shift which privileges mutual vulnerability and interdependence as the new ‘norm.’ Time to cancel that subscription to the cult of normalcy, people. I don’t believe anything less will do.

I realized that I’ve been playing into these notions of the “cult of normalcy” even in the way I describe this internship to people. The key line I always used was: “I’m reading and writing about how the Christian church can learn to better serve individuals with disabilities.” This sort of service language only widens the gap between “us normal people over here” and “those disabled people over there.” I no longer think that learning how to better serve people with disabilities is what the Church needs. This is arguably a dangerous attitude which can give us a messiah complex and turn disability into something to be treated rather than a person to be known. I believe what Christians need is nothing less than an entirely new way of thinking about and relating to people, including themselves. This requires a fundamental anthropological shift which privileges mutual vulnerability and interdependence as the new ‘norm.’ Time to cancel that subscription to the cult of normalcy, people. I don’t believe anything less will do. I learned something valuable in the body of Christ this past morning in church. I learned the necessity of being confronted with my own racial prejudices particularly within a multiethnic church. I participated in lived theology as a church, a living chaotic body that mysteriously communes together with the Lord. As a structure we were able to acknowledge our broken world, our broken bodies, collectively repent, accept grace, and begin to turn away from our sin. That is the goodness of the church; it has power as a corporate body, given life through individuals, to enact radical change in ourselves and as a body.

I learned something valuable in the body of Christ this past morning in church. I learned the necessity of being confronted with my own racial prejudices particularly within a multiethnic church. I participated in lived theology as a church, a living chaotic body that mysteriously communes together with the Lord. As a structure we were able to acknowledge our broken world, our broken bodies, collectively repent, accept grace, and begin to turn away from our sin. That is the goodness of the church; it has power as a corporate body, given life through individuals, to enact radical change in ourselves and as a body. In her landmark work of womanist theology, Sisters in the Wilderness, Dolores Williams connects the story of Hagar, with which the black community has long identified, to black women’s experience of surrogacy/motherhood, oppression, and survival in the United States. She points out that Hagar is the only character in the entire Bible who has the privilege of naming God. When Hagar flees a second time, this time with her son Ishmael, God enables their survival by helping Hagar find water for her dying child, and “God was with the boy as he grew up” (Gen. 21:20). This God, Williams claims, is different from the “malestream” God of Abraham. She is different even from the God of black (male) liberation theology, who is always portrayed as the Great Liberator of the Exodus, in spite of stories like Hagar’s (in which God’s provision does not come in the form of liberation from slavery). Hagar’s God is not the God whose authority Sarah probably cited when she forced Hagar to be Abraham’s concubine. Hagar’s God is the one who sees her.

In her landmark work of womanist theology, Sisters in the Wilderness, Dolores Williams connects the story of Hagar, with which the black community has long identified, to black women’s experience of surrogacy/motherhood, oppression, and survival in the United States. She points out that Hagar is the only character in the entire Bible who has the privilege of naming God. When Hagar flees a second time, this time with her son Ishmael, God enables their survival by helping Hagar find water for her dying child, and “God was with the boy as he grew up” (Gen. 21:20). This God, Williams claims, is different from the “malestream” God of Abraham. She is different even from the God of black (male) liberation theology, who is always portrayed as the Great Liberator of the Exodus, in spite of stories like Hagar’s (in which God’s provision does not come in the form of liberation from slavery). Hagar’s God is not the God whose authority Sarah probably cited when she forced Hagar to be Abraham’s concubine. Hagar’s God is the one who sees her.

Rachel Prestipino is a third year student majoring in religious studies and global development studies. She is particularly interested in notions of human dignity, especially with regard to women, as they are presented by various Christian theologies. She is spending her summer serving women who have experienced violence and exploitation in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco.

Rachel Prestipino is a third year student majoring in religious studies and global development studies. She is particularly interested in notions of human dignity, especially with regard to women, as they are presented by various Christian theologies. She is spending her summer serving women who have experienced violence and exploitation in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco. Melina Rapazzini is a third year student majoring in religious studies and nursing, which has naturally resulted in a passion for studying the intersection between ethics and direct patient care. A native from the San Francisco Bay Area, Melina is excited to live in in Oakland and work with New Hope Covenant Church to develop a reading, art, and gardening program for inner city refugee children. Melina is mostly looking forward to learning from these children how to see and understand the Kingdom of God in a neighborhood with historically one of the highest rates of robbery in the United States.

Melina Rapazzini is a third year student majoring in religious studies and nursing, which has naturally resulted in a passion for studying the intersection between ethics and direct patient care. A native from the San Francisco Bay Area, Melina is excited to live in in Oakland and work with New Hope Covenant Church to develop a reading, art, and gardening program for inner city refugee children. Melina is mostly looking forward to learning from these children how to see and understand the Kingdom of God in a neighborhood with historically one of the highest rates of robbery in the United States.

I realized that I’ve been playing into these notions of the “cult of normalcy” even in the way I describe this internship to people. The key line I always used was: “I’m reading and writing about how the Christian church can learn to better serve individuals with disabilities.” This sort of service language only widens the gap between “us normal people over here” and “those disabled people over there.” I no longer think that learning how to better serve people with disabilities is what the Church needs. This is arguably a dangerous attitude which can give us a messiah complex and turn disability into something to be treated rather than a person to be known. I believe what Christians need is nothing less than an entirely new way of thinking about and relating to people, including themselves. This requires a fundamental anthropological shift which privileges mutual vulnerability and interdependence as the new ‘norm.’ Time to cancel that subscription to the cult of normalcy, people. I don’t believe anything less will do.

I realized that I’ve been playing into these notions of the “cult of normalcy” even in the way I describe this internship to people. The key line I always used was: “I’m reading and writing about how the Christian church can learn to better serve individuals with disabilities.” This sort of service language only widens the gap between “us normal people over here” and “those disabled people over there.” I no longer think that learning how to better serve people with disabilities is what the Church needs. This is arguably a dangerous attitude which can give us a messiah complex and turn disability into something to be treated rather than a person to be known. I believe what Christians need is nothing less than an entirely new way of thinking about and relating to people, including themselves. This requires a fundamental anthropological shift which privileges mutual vulnerability and interdependence as the new ‘norm.’ Time to cancel that subscription to the cult of normalcy, people. I don’t believe anything less will do.

On the Lived Theology Reading List this week is PLT Contributor

On the Lived Theology Reading List this week is PLT Contributor