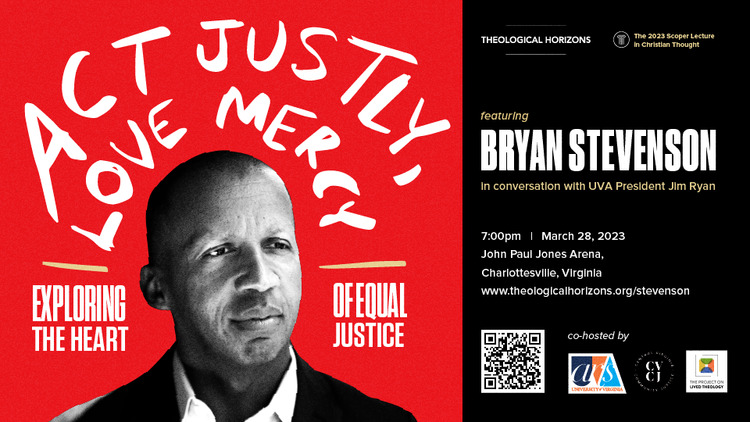

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA – Theological Horizons, in partnership with Central Virginia Community Justice, Project on Lived Theology at UVA, and UVA Arts, is mobilizing local churches, justice organizations, student groups and community activists to welcome Equal Justice Institute Founder and New York Times bestselling author Bryan Stevenson for the 2nd annual Scoper Lecture in Christian Thought at 7:00 pm on Tuesday, March 28, 2023 in the John Paul Jones Arena.

The address, titled “Act Justly, Love Mercy: Exploring the Heart of Equal Justice,” will explore the spiritual foundations of Mr. Stevenson’s work as a pioneer in the criminal justice field addressing systemic racial injustice and working on behalf of those who have been wrongly convicted or unfairly sentenced. To date, nearly 2500 of the arena’s 3800 available seats have been sold for this unprecedented event, which has also mobilized almost 50 Community Partners and Event Sponsors that represent a diverse range of local schools, faith groups, justice and community organizations.

“Bryan Stevenson is an inspiration for so many of our students, and his message of hope is so timely for our wider university community which is still grieving from the tragic shooting last fall,” said Karen Wright Marsh, Executive Director for Theological Horizons. “Seeing the way groups and individuals from across the ideological spectrum are rallying to support this event is such an encouragement that despite our painful history, differences, and divisions we can still connect around a shared desire for justice and mercy to prevail.”

Mr. Stevenson’s bestselling book, Just Mercy, recounts the story of one of his first cases in which he secured an acquittal for Walter McMillan, an African-American man sentenced to death for a murder he did not commit. In 2019 the story was adapted into the box-office hit Just Mercy and the HBO documentary True Justice.

“To see this community coming together around the message of racial justice is really hopeful,” said Eddie Howard, Executive Director of Abundant Life Ministries and a member of the event’s Host Committee. “We’ve tolerated a lopsided justice system for too long, harming our most vulnerable communities. It’s time we follow Mr. Stevenson’s example and listen to what our faith has to say about caring for ‘the least of these’.”

The March 28 event is the second annual Scoper Lecture Series in Christian Thought, which brings eminent scholars to the University of Virginia to explore the breadth of Christian expression in science, medicine, culture, and the arts. The series is generously funded by UVA parent and past UVA assistant professor of ophthalmology Stephen Scoper, M.D. and his wife Nancy. Last year’s speaker was New York Times bestselling author and Duke associate professor, Kate Bowler, PhD.

“Too often, faith perspectives can be unhelpfully narrow,” Dr. Scoper said. “It’s so important we hear from people like Bryan whose inspiring work can challenge and stretch our understanding of what really matters.”

This event is open to the public. Tickets may be purchased for $8 (plus fees) via Ticketmaster at www.theologicalhorizons.org/Stevenson. For groups of 20 or more tickets are discounted to $6/person (plus fees) or guests may purchase a livestream ticket for $4. This event will not be recorded.

The Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia is a research initiative, whose mission is to study the social consequences of theological ideas for the sake of a more just and compassionate world.