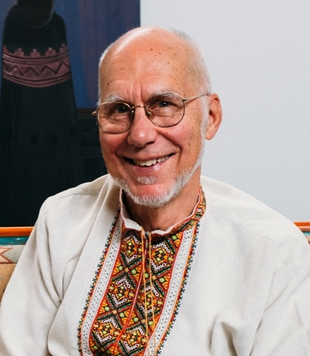

On October 8, 2024, Dr. Larry Rasmussen joined a graduate seminar in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia called Theologies of Resistance and Reconciliation to speak to the class about the thought and life of Niebuhr. The course was rolled out twenty years as a graduate seminar on Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King. Jr. and has expanded over the years to include Reinhold Niebuhr and Dorothee Soelle.

Dr. Larry Rasmussen is the Reinhold Niebuhr Professor Emeritus of Social Ethics at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Rasmussen’s first book – his revised doctoral dissertation – was based on a fellowship year in Berlin in 1969 during which he conducted oral interviews wit Bonhoeffer’s students, fellow conspirators, family members, and allies in the Kirchenkampf. The landmark book, Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Reality and Resistance. Originally was published in 1972, and reissued by Westminster John Knox Press in 2005. Larry has also served as an editor and consultant to the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works Translation Project.

Professor Rasmussen is a lay theologian of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. His current work in Christian ethics includes analysis of power, methodological issues in Bible and ethics, and reflections on technology and ecology. His volume, Earth Community, Earth Ethics (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1996), won the prestigious Grawemeyer Award in Religion of 1997. He served as a member of the Science, Ethics, and Religion Advisory Committee of the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) and was a recipient of a Henry Luce Fellowship in Theology, 1998-99, the Burnice Fjellman Award for Distinguished Christian Ministries in Higher Education, and the Joseph Sittler Award for Outstanding Leadership in Theological Education. From 1990-2000 he served as co-moderator of the WCC unit, Justice, Peace, Creation. He and Nyla live in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Excerpt: “Pandemics that have deep roots and institutional legs like the pandemic of racism, take a long time to eradicate. Victories come in fits and start in context after being engaged anew over and again, not least because the poisonous virus develops new variant strains. This means you should celebrate victories when you can rest up, return to the struggle with vigor, and pass the torch when you must.”

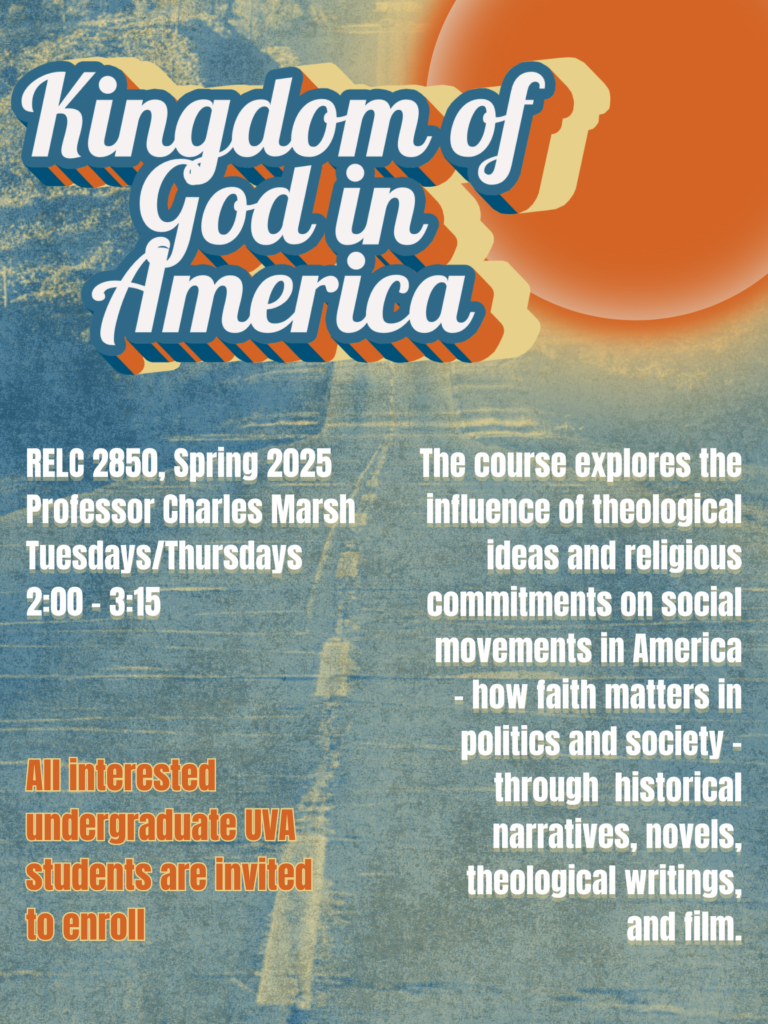

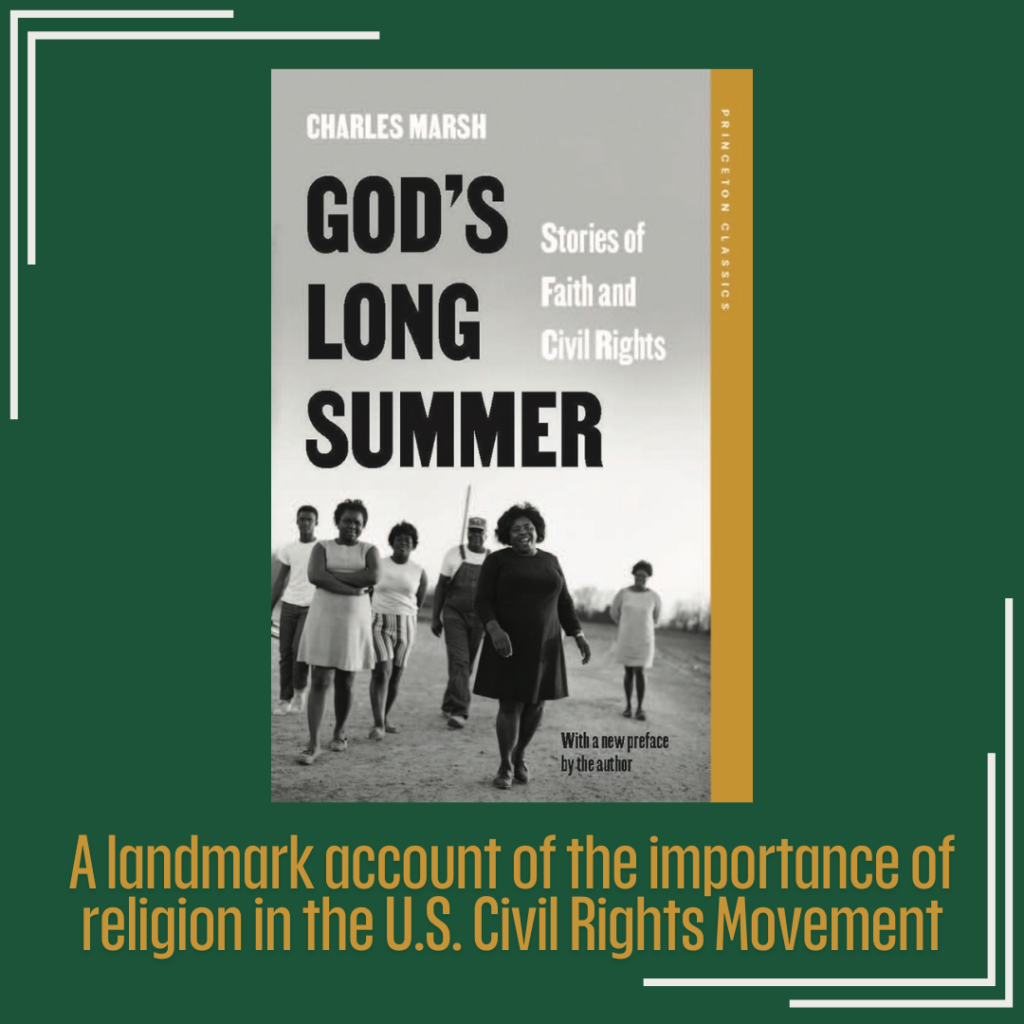

The Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia is a research initiative, whose mission is to study the social consequences of theological ideas for the sake of a more just and compassionate world.