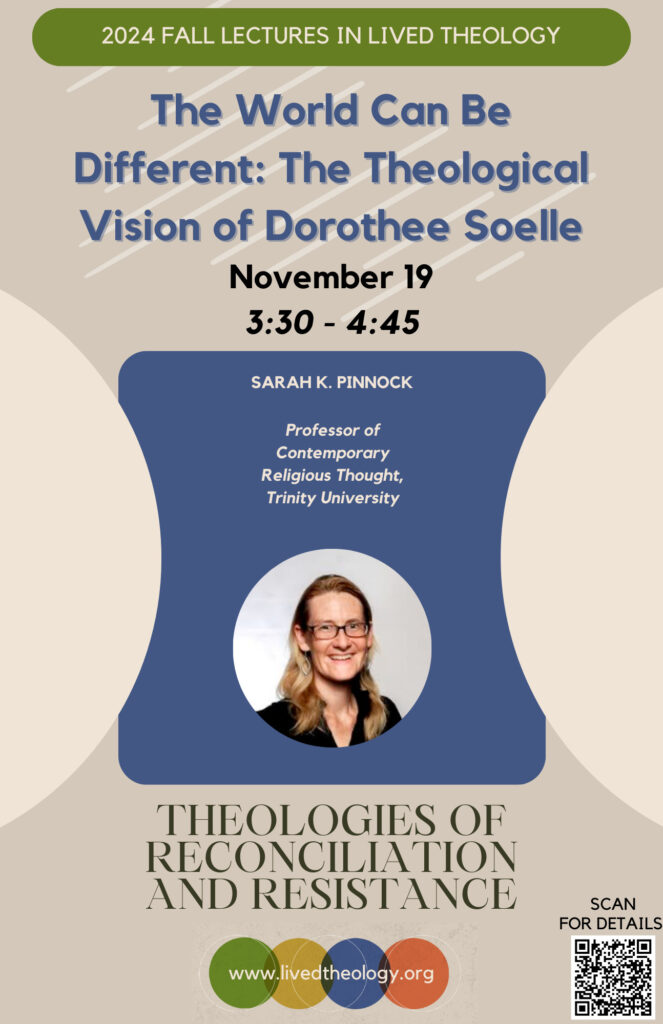

On November 19, 2024, Professor Sarah Pinnock joined the UVA graduate seminar Theologies of Resistance and Reconciliation to talk about the life and thought of Dorothee Soelle.

Dr. Sarah Pinnock is professor of contemporary religious thought at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. Sarah was born in New Orleans in 1968-67, where her father, a Baptist theologian and influential, evangelical thinker, Clark Pinnock, taught theology. When she was her family moved back to their native Canada, first to Vancouver, and later to Toronto.

After undergraduate and M.A. studies at MacMaster University, Sarah began doctoral studies in philosophical theology at Yale University under the tutelage of Louis Dupree. During a research year in Germany, Sarah served as Dorothee Soelle’s assistant.

Her research on Soelle and more broadly on Christian responses to the Holocaust, culminated in her doctoral dissertation, which led in turn to her first book, Beyond Theodicy, Christian Continental Thinkers Respond to the Holocaust.

Dr. Pinnock joined the faculty at Trinity University in 2000. Her book The Theology of Dorothee Soelle is a stellar collaboration of essays and the basis of her presentation this afternoon.

On the shape of Soelle’s thought, Pinnock writes: “Soelle’s mysticism and christology responds to critiques in modernity. God is not the explanation for scientific unknowns, or what Bonhoeffer calls ‘the God of the gaps.’ She also rejected the image of God as the ruler of history… Soelle proposed a nontheistic christology that opens up a vision of God in which God is dependent, and our actions represent God in the world. We are each unique contributors to the work of God in the world.”

Listen to the event here

Watch the event here

The Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia is a research initiative, whose mission is to study the social consequences of theological ideas for the sake of a more just and compassionate world.