Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation

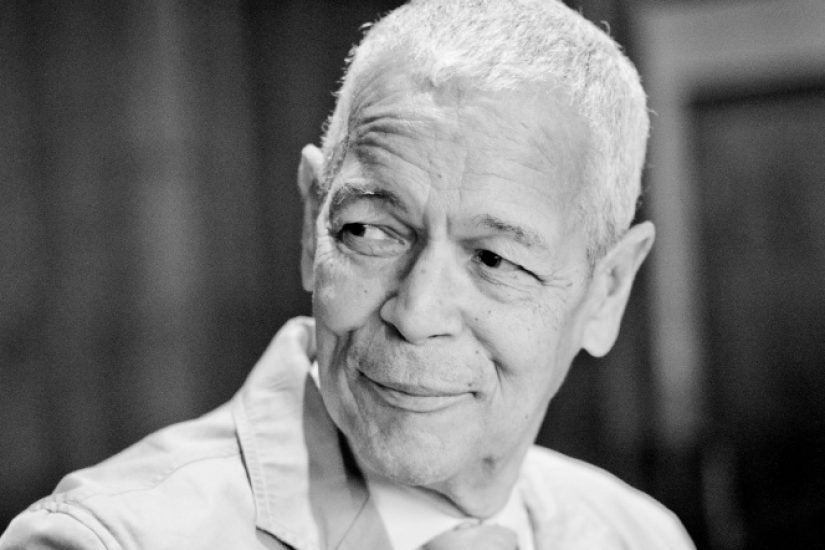

The Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation at the University of the South is a six-year initiative investigating the university’s historical entanglements with slavery and slavery’s legacies. This project seeks to honor Houston Roberson, a long time professor and the first African American to earn tenure at the University of the South. His teaching was devoted to the subjects of African American history and culture.

In 2009 Dr. Roberson published an essay, “The Problem of the Twentieth Century: Sewanee, Race and Race Relations,” in the University’s sesquicentennial volume, Sewanee: Perspectives on the History of the University of the South. This essay directly addressed the history of race on campus and the larger community. It was the first piece of written scholarship to tackle these subjects, and helped to change how we think about the history of this community and university.

The Roberson Project hosts events related to scholarship and social justice, confronting history to seek a “more just and equitable future for our broad and diverse community.” These initiatives are a memorial to Roberson, honoring his historic contributions to the University of the South. This initiative also seeks to create a comprehensive history of the University of the South in relation to slavery, race, and racial injustice. In addition, it will work with existing campus groups to develop curricula and programs to enrich perspectives and equitable opportunities for students.

Fellow travelers are scholars, activists, and practitioners that embody the ideals and commitments of the Project on Lived Theology. We admire their work and are grateful to be walking alongside them in the development and dissemination of Lived Theology.